|

| Image licensed to The Court Jeweller; do not reproduce |

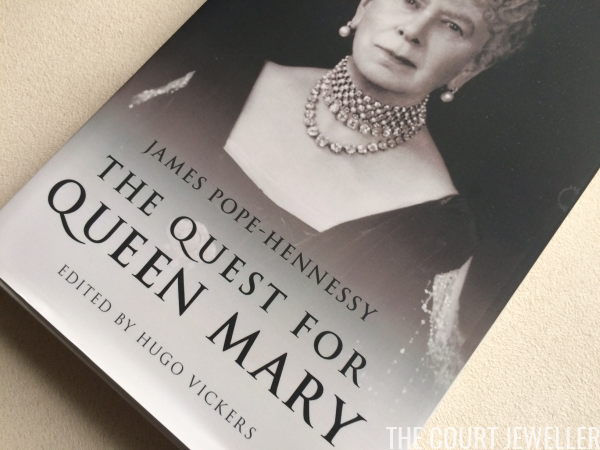

Book Review: The Quest for Queen Mary (2018)

|

| The Quest for Queen Mary (Photo: The Court Jeweller. Do not reproduce) |

When I was considering possible selections for this month’s book club pick, there was one book that I really wanted to select — but, for practical reasons, decided I couldn’t. The latest from Hugo Vickers, The Quest for Queen Mary, is an absolutely fantastic read, even though it’s currently a bit tough to get a hold of.

|

| The Quest for Queen Mary (Photo: The Court Jeweller. Do not reproduce) |

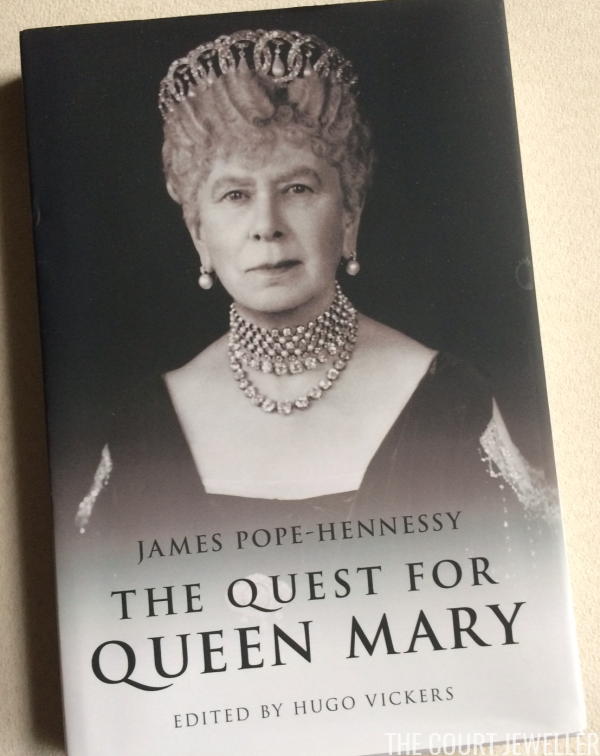

The Quest for Queen Mary combines two of my favorite things: fascinating tidbits about royals and behind-the-scenes views of historical work. The book tells the story of the writing of James Pope-Hennessy’s famous biography of Queen Mary through a carefully presented look at his unpublished research notes. Hugo Vickers, a talented royal biographer himself, has compiled and contextualized Pope-Hennessy’s accounts of interviews with the people from Queen Mary’s world, including a whole lot of royals and aristocrats. The result is a picture not only of the biographer’s craft but also of the royal family as it was in the late 1950s. (The Crown only wishes it were this interesting, honestly.)

|

| Princess May, ca. 1893 (Grand Ladies Site) |

We learn some truly fascinating pieces of royal information in the book, including many tidbits that Pope-Hennessy chose to leave out of his book. The Quest for Queen Mary spills the dirt on royal personalities (the cold parenting of George and Mary, the strange aloofness of Queen Elizabeth II, the jovial friendliness of Alice Athlone, the odd drawl of the Duchess of Windsor). It dishes on royal residences (the coziness of Balmoral and Osborne, the eeriness of Sandringham). It whispers about Mary’s carefully-crafted appearance (the fact, for example, that she had separate wigs for day and night occasions, and the deliberate height and shape of her hats, designed not to overwhelm her shorter husband). And it even speaks forthrightly about royal scandals (the illegitimate Mecklenburg-Strelitz baby, the Duke of Kent’s drug addiction, Princess May’s first love, the madness of the Duke of Teck, Queen Mary’s secret love affair with Henry of Battenberg).

|

| Queen Mary wearing the Girls of Great Britain and Ireland Tiara (Grand Ladies Site) |

The best moment of the book, without a doubt, is Pope-Hennessy’s recounting of his visit to Barnwell Manor, home of the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester. There, he stayed with the Duke and Duchess (parents of the present Duke) and Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone. His depiction of all three is masterful, and the scene where the four work together on the garden — all the while chatting about the family and the people who surrounded them — is just amazing. The Gloucester set piece is worth the price of admission alone, but the fact that it’s accompanied by so many other fascinating moments (the visit with Prince Axel of Denmark, the luncheon at Balmoral, the trip to see the Princess of Wied) makes the book absolutely worth buying. And, speaking of The Crown, fans of Tommy Lascelles will be delighted to see him pop up over and over again in this book, too.

|

| Queen Mary wearing Queen Alexandra’s Kokoshnik — and a boatload of other royal jewels! — ca. 1930s (Wikimedia Commons) |

Pope-Hennessy’s biography of Queen Mary is held up as one of the best examples of the genre, and Vickers’s book is a wonderful companion to it, but it can also be read as a standalone text. Anyone interested in Queen Mary, the world of royalty in the twentieth century, or biography as an art will not be disappointed with this book.

|

| The Quest for Queen Mary (Photo: The Court Jeweller. Do not reproduce) |

So, all that said, why didn’t I pick this one for the August book club selection? It’s simple — tracking down a copy is a bit difficult, especially for those of us who don’t live in Britain. The book is currently available in the US on Amazon from a third-party seller, but I ended up buying my copy straight from the publisher. That meant paying for shipping from Europe, but the cost just about evened out in the end. If you can get your hands on this book, I’d highly recommend it — and I’m hoping that an American publisher will make the book even more accessible for Yanks in the near future, too.

The Sutherland Ruby, Diamond, and Pearl Necklace

|

| Cate Gillon/Getty Images |

Few royal women have inspired more myth, legend, and furor than Marie Antoinette, the French queen whose life ended on a guillotine in the midst of revolution. The extravagance of her life, and the notoriety of her death, have made objects associated with her into something like relics. In particular, jewels connected with the tragic queen are incredibly sought after. Perhaps it’s a surprise, then, that this British aristocratic ruby and diamond necklace — which is also set with Marie Antoinette’s pearls — didn’t make it off the auction block.

|

| Detail of Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s Marie-Antoinette dit à la Rose, ca. 1783 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Before we get to the necklace itself, we need to turn our time machines back to 1792, the year before Marie Antoinette’s execution. In the wake of revolution, the French monarchy was abolished, and in response to the imprisonment of the royal family, the British embassy in Paris was formally withdrawn. The British ambassador, Lord Gower, was married to a woman who held an aristocratic title in her own right: Elizabeth Gordon, 19th Countess of Sutherland. Lord Gower and Lady Sutherland had arrived in Paris in June 1790, and she was impressed by Marie Antoinette during her presentation at court that summer, noting in a letter that the queen “had so much grace and [was] so pleasing.”

|

| Detail of Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of Lady Sutherland (Wikimedia Commons) |

Elizabeth remained in contact with Marie Antoinette throughout her husband’s short, tumultuous diplomatic tenure in France. When the family was preparing to return to London in September 1792, Elizabeth visited the royals. She reported in her letters back to England that the royal family was “safe” but thought that their treatment was not appropriate. Elizabeth — who had a son the same age as Marie Antoinette’s own son, the Dauphin — took pity on the queen and sent her clothing and linens to help make them more comfortable. The generosity was long remembered, according to the Sutherland family, and later acknowledged by Marie Antoinette’s daughter, the Duchess of Angoulême.

|

| Georges Cain’s Marie-Antoinette sortant de la Conciergerie, le 16 octobre 1793, ca. 1885 (Wikimedia Commons) |

At some point during these encounters with the royal family, Marie Antoinette pressed Elizabeth into a secret mission. According to Christie’s, “Marie Antoinette gave Lady Sutherland a bag of pearls and diamonds for safe keeping. Anyone caught in possession of this jewellery risked severe punishment. However, the wife of the British Ambassador had diplomatic immunity and was one of the few who could be trusted to return the jewels when the Queen escaped.” Elizabeth successfully smuggled the jewels along with her when she returned to England.

|

| Cate Gillon/Getty Images |

We all know, though, that such an escape never happened. Marie Antoinette was executed in Paris in October 1793. Back in London, Elizabeth Sutherland was caught up in the social whirl of the time, hosting parties and entertaining some of the most important people of the day. (Unfortunately, she and her husband were also deeply involved in the Highland Clearances in her native Scotland, depriving tenants of their established farms and homes to make way for larger farms.) As Marie Antoinette was never going to be able to retrieve her gems, the Sutherlands kept them — and, eventually, used them.

|

| ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images |

In 1849, Elizabeth’s grandson, the Marquess of Stafford (later 3rd Duke of Sutherland), married Anne Hay-Mackenzie (who was later created Countess of Cromartie in her own right). For the occasion of their wedding, a cache of gray pearls from Marie Antoinette’s collection was used to make a new necklace. Christie’s describes the necklace as having “a fringe of twenty one graduated drop-shaped grey natural pearls, each suspended from an old-cut diamond collet surmount to the diamond ribbon which intertwines the ruby collar. The collar is set with twelve button-shaped grey natural pearls which are mounted in gold. The pearls, which date to circa 1780, belonged to Marie Antoinette.”

|

| Cate Gillon/Getty Images |

On first glance, the necklace looks much more modern than it really is — the zig-zag design of the piece anticipates some of the geometric, architectural trends of twentieth-century design. But when you see the piece up close, the setting of the gemstones confirms its nineteenth-century creation date.

|

| Cate Gillon/Getty Images |

The family managed to hang on to the necklace for a very long time. In the autumn of 2007, Christie’s announced that the Sutherland necklace (marketed as “Marie Antoinette’s Pearls”) would be presented for auction at a Magnificent Jewellery sale in London in December of that year. The press materials for the sale listed the necklace as “property of a nobleman,” but quotes from Christie’s staff revealed that the necklace was “fresh to the market” and the pearls had “been in the same family for over 200 years.”

|

| Cate Gillon/Getty Images |

The necklace’s auction estimate was set in a range between £350,000 and £400,000. When the auction took place on December 12, however, the piece failed to meet its set minimum, and it was subsequently withdrawn. This was an unusual turn of events for a piece of jewelry with a documented, proven connection to Marie Antoinette, and to my knowledge, we haven’t heard anything more about it in the decade that has elapsed since.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- …

- 857

- Next Page »