|

| Department of Defense/Wikimedia Commons |

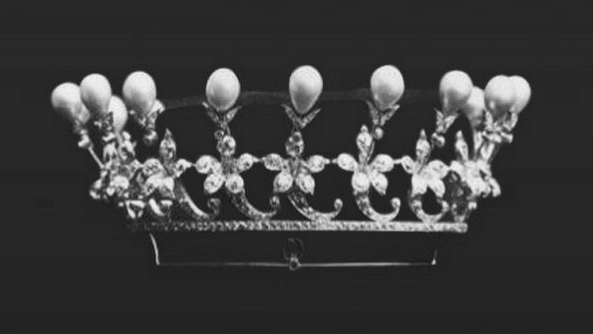

Empress Alexandra’s Boucheron Coronet

|

| Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia wears her Boucheron coronet in a portrait, ca. 1914 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Romanov jewelry vaults were massive, including some of the most elaborate diadems and tiaras worn at the turn of the twentieth century. But Russia’s last empress was partial to a much smaller sparkler: a sentimental pearl and diamond coronet.

|

| Empress Alexandra’s pearl and diamond coronet |

The tiny tiara, composed of diamond floral and scroll designs surmounted by a series of natural pearls, was made by Boucheron in the 1890s. In 1894, shortly after his proposal to Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine was formally accepted, the future Tsar Nicholas II purchased the coronet for his fiancee as an engagement present.

|

| Alexandra wears the coronet, ca. 1898 (Grand Ladies Site) |

The purchase of the diadem actually happened in Britain. Nicholas visited Alix and her grandmother, Queen Victoria, at Windsor in the summer of 1894, following the official engagement annoucnement. In his book on the Romanov jewels, Stefano Papi includes an image of a note written from Windsor Castle on Nicholas’s behalf by Prince Dmitry Borisovich Galitzine. The note requests that Mr. Aubert, a representative from Boucheron, should bring “the things you should like to show” the future tsar to Windsor, scheduling the appointment for July 17, 1894, at five o’clock in the evening. Presumably Nicholas purchased the coronet from Aubert at Windsor Castle on that date. (The date would later be an unfortunately significant one for Nicholas, Alix, and their children.)

|

| Alexandra wears the coronet, ca. 1906 |

Alix, who took the name Alexandra Feodorovna when she married Nicholas in November 1894, wore the little pearl and diamond coronet for the rest of her life. Here, she wears the coronet in one of a series of portraits taken in 1906, pairing it with other pieces of pearl jewelry.

|

| Alexandra wears the coronet, ca. 1906 |

She also wore the tiara in other poses from this portrait series, including photos taken with her son, Grand Duke Alexei, and her sister, Princess Louis of Battenberg.

|

| Alexandra wears the coronet in a family portrait, ca. 1914 |

Near the end of her life, Alexandra wore the coronet for another family portrait session, which took place in either 1913 or 1914 (sources differ — Papi says 1914). Here, she poses with all four of her daughters: Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia.

|

| Alexandra wears the coronet in a family portrait, ca. 1914 (Wikimedia Commons) |

And here, she wears the coronet with her entire family, including Tsar Nicholas II and Grand Duke Alexei. There’s something particularly poignant about her decision to continue wearing her tiny engagement coronet even after she was empress of one of the world’s largest nations. And, of course, there’s more poignancy about the coronet itself, which — as you may have already guessed — was confiscated by the Bolsheviks and has not been seen since, vanishing into the mists of time just like its famous wearer.

Jewel History: State Performance at the Opera (1893)

|

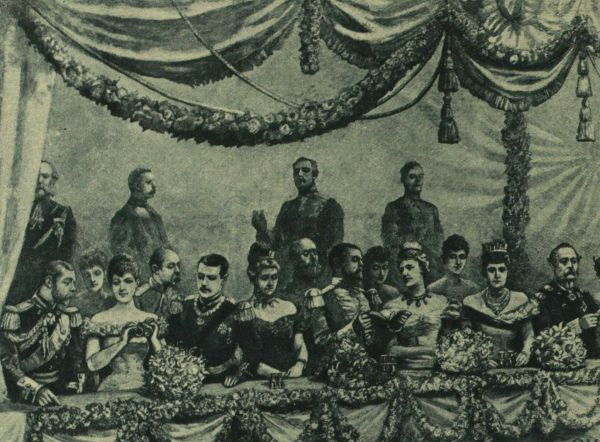

| Guests in the royal box at the Opera House in Covent Garden on 4 July 1893, just before the royal wedding, in an illustration from the Illustrated London News |

The State performance given at the Opera House last night in honour of the Duke of York [1] and the Princess May [2] differed in one important respect from previous “gala” representations held in the same building. Hitherto, or at any rate during the past thirty years, these “Command” performances have taken place only on the visit of some foreign potentate, such as the late Czar, the German Emperor, or the Shah. The event of last evening, when the large majority of the illustrious company in the Royal box were connected by ties of kinship with our own Royal family, was, on the other hand, essentially a national and almost a domestic gathering — a compliment paid by London Society to the English Prince and Princess whose wedding will be celebrated tomorrow.

Not that the splendour of the scene was diminished a whit on this account. It may indeed be said, without the slightest fear of contradiction, that a more brilliant spectacle has never before been witnessed at Covent Garden. As to the galleries, which were crammed to their last seats, the crowds had been waiting outside the doors from one o’clock in the afternoon. The floor of the house and the boxes were filled by the flower of the English aristocracy, the ladies resplendent in costly costumes and rare diamonds, while the gentlemen, although Court dress was not unduly insisted upon, were almost without exception clad in either levee dress or uniform.

|

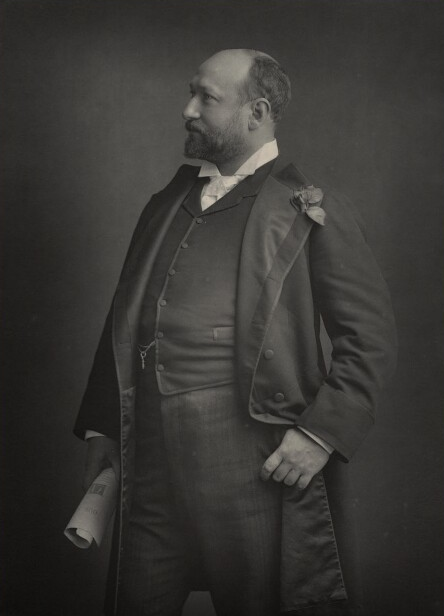

| Sir Augustus Harris, photographed in February 1889 (© National Portrait Gallery, London) |

This time Sir Augustus Harris [3] had not depended upon contractors, but had resolved personally to superintend the dressing of his theatre, the whole of the decorations, with the exception of the flowers, which were supplied by Messrs. Gerard, being arranged by the staff of the Opera House. An army of men had taken possession of the building immediately after the close of the performance of “Tannhäuser” on Monday, and the manager himself remained in the theatre all night to superintend the work. By six o’clock last evening the entire task was finished. While the audience were waiting for the arrival of the Royal party an excellent opportunity was afforded of viewing the house and its decorations.

At previous gala representations the “Lily” of Persia and the “Cornflower” of the Hohenzollerns prominently figured, but last night the auditorium was converted into a huge “Rosery of Scented Thorn.” The White Rose of York was of course strongly in evidence, relieved by roses of pink and red, buried in maidenhair and other ferns, and twisted into robes of flowers hung around each circle. The box partitions of the pit, grand and first tiers were outlined with these garlands, but in the higher circles where real flowers would have been damaged by the heat, festoons of artificial roses and greenery were artistically arranged along the box fronts. On the ledge of every box rested a couple of huge bouquets, with streamers of silk of the national colours. The auditorium was literally scented with these flowers, of which some tens of thousands were used, so that during the past day or two there has been quite a “corner” in roses in Covent-garden market.

In the centre of the grand tier half a dozen boxes had been removed to make way for the Royal saloon. Here, as was abundantly clear, the fact that the present was a marriage celebration had been kept prominently in view. The framework of the Royal saloon was of white satin, held up by ropes of corded silk, and profusely decorated with flowers, the initials “G” and “M” in pink carnations being at each corner, while the front was surmounted with the Royal arms. The lining of the box was of rainbow silk, gathered up in the centre of each panel to a mirror, outlined in flowers, and illuminated with electric lights. Festoons of orange blossoms crossed the box in all directions, while here and there peeped out tiny electric lamps of red, white, and blue, with the daintiest imaginable effect. Sir Augustus Harris and his staff must cordially be congratulated on having so admirably carried out an idea as pretty as it was tasteful and artistic.

In the entrance hall and grand staircase an even more elaborate scheme of decoration had been devised. The ordinary carriage way had, for the moment, been completely abolished, and, hung with red baize and profusely decorated with ferns and flowers, it was converted into an entrance hall. Here were stationed a Guard of Honour of the First Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, under Major Legge, with the band of the same regiment under Mr. Thomas. The Royal guests, as they arrived, passed into the crush-room, which was decorated with flowers, shrubs, and tall palms, and cooled by huge blocks of ice, surrounded by ferns and illuminated with electric and other lamps. Flowers were arranged on each side of the grand staircase, where the grizzled warriors of the Yeomen of the Guard, each holding his tall halbert in his hand, were drawn up.

|

| The Tiffany opera glasses given as a wedding present to Princess May by Sir Augustus Harris and Lady Harris, housed today in the Royal Collection |

Over the foot of the staircase, thanks to another particularly happy idea, was hung a huge marriage bell, some four feet in diameter, constructed of white roses, the bell-ropes being of orange blossoms, and the clapper an electric light. At the entrance of the Royal reception room was another of these marriage bells, and here, as the Princess may crossed the threshold, stood Sir Augustus Harris, with a tasteful marriage gift — an opera-glass of gold, the rims picked out in pearls and enamels, and the barrels and screws studded with diamonds. The ordinary grand tier refreshment saloon was for the evening set apart as a Royal reception room, the further end being made into a buffet, as on all State occasions, duly furnished with refreshments by the Board of Green Cloth, while the space over the entrance hall, hung with blue and profusely decorated with flowers, had been divided into two, the nearer half being a boudoir for the ladies, and the further a smoking room for the gentlemen of the Royal party.

The guests began to arrive nearly an hour before the performance commenced, and by a quarter-past eight the word of command for a Royal salute announced the Duke of Cambridge [4], who was the first-comer of the Royal party. The other Royal guests now began to arrive in rapid succession. The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh [5] passed along the entrance hall, and soon a volley of cheers announced the Duke and Duchess of Teck [6], Princes Adolphus [7], Francis [8], and Alexander [9], and the Princess May. Then came Prince and Princess Henry of Battenberg [10], Princess Christian [11], and the Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz [12], and Prince Christian [13] leading the Grand Duke [14]. The Duke and Duchess of Connaught [15] passed in almost unnoticed, and so did the Duke and Duchess of Fife [16], who arrived punctually at half-past eight.

Seven minutes afterwards the band of the Coldstreams struck up “God Save the Queen,” the Guard again presented arms, and the bulk of the Marlborough House party appeared. First came the Prince of Wales [17], in Field-Marshal’s uniform, escorting the Queen of Denmark [18], and the King of Denmark [19] escorting the Princess of Wales [20]. The Princesses Victoria [21] and Maud [22] walked together, and were followed by the Duke of York in naval uniform, and the Czarewitch [23] in the long, red gown, which we believe is the dress uniform of a General of the Cossacks. A short pause was made in the Reception Room, where, this being a State performance, a regular procession was formed to the Royal box. The Prince of Wales (conducted by the Lord Chamberlain, who wand in hand, and walked backwards) led the way, and as his Royal Highness appeared, the band of the Opera House, led by Signor Mancinelli [24], struck up the National Anthem, and the electric lights went up, first in the Royal box, and immediately afterwards all over the house.

|

| Detail from the Illustrated London News depiction of the royal box, featuring the Tsarevich (later Nicholas II of Russia), Queen Louise of Denmark, the Princess of Wales (later Queen Alexandra), and King Christian IX of Denmark |

The order of procession had been supplied to the Royal party, who were exactly forty in all, and thus there was no confusion. The Prince of Wales occupied the extreme left-hand corner of the box looking at the stage, and then in order in the front row successively came the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the Duchess of Teck, the King of Denmark, the Princess of Wales, the Queen of Denmark (occupying the place of honour in the centre of the box), the Czarewitch, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the Grand Duke of Hesse, the Princess May, and the Duke of York. In the second row, and in the same order, counting from the left, came Prince Waldemar of Denmark [25], the Duchess of Edinburgh, Prince Albert of Belgium [26], the Duchess of Connaught, Prince Philip of Saxe-Coburg [27], Princess Christian, the Duke of Edinburgh (seated immediately behind the Queen of Denmark), Princess Louise of Lorne [28], the Duke of Connaught, Princess Henry of Battenberg, Prince Christian, the Duke of Cambridge, the Duchess of Fife, and Prince Henry of Battenberg.

In the last row were seated the Duke of Teck, the Marquis of Lorne [29], Prince and Princess Edward of Saxe-Weimar [30], and some of the younger members of the Royal family, such as the Princesses Victoria and Maud of Wales, the sons of the Duke of Teck, the Princess Victoria of Edinburgh [31], Prince Albert [32] and Princess Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein [33], and Prince and Princess Louis of Battenberg [34]. The spectacle, as this imposing array of Royalties took their places, the whole of the audience upstanding, was perhaps as brilliant as anything that could have been furnished in any European capital. At the close of “God Save the Queen,” there were loud cheers from the gallery, and Signor Mancinelli, without further delay, gave the signal for the overture to the opera.

|

| Detail from the Illustrated London News depiction of the royal box: the Duke of York (later King George V), Princess May of Teck (later Queen Mary), Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse and by Rhine, and Grand Duchess Augusta of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

The Royal party being seated, although there was some show of watching the performance, it may be safely said that the interest of the major portion of the audience was chiefly centred in the spectacle in the auditorium. The dresses were well worthy the occasion. The Princess Edward of Saxe-Weimar wore black with a very magnificent tiara and necklace of emeralds and diamonds, and the Duchess of Edinburgh soft pink brocade with a tiara of splendid diamonds and a necklace and pendant of equally large and costly brilliants. Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh was in pale blue, the Duchess of Teck was in purple, with diamond tiara, necklace, and clusters of diamonds on the bodice of her dress, and the Princess May was dressed in pale blue brocade with trimmings of pale blue and rose-pink, and wearing very few jewels.

Louise, Marchioness of Lorne, looked very handsome and animated in a gown of cream-coloured satin with a high tiara of diamonds, and the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was in red brocade with a wonderful tiara and necklace of great diamonds. The Duchess of Connaught was in white with a diamond aigrette, and the Duchess of Fife in a simple, but effective and becoming dress of white brocade and a tiara and necklace of diamonds. The Princess of Wales wore pale silver-grey satin and a splendid diamond tiara and necklace. Georgina Countess of Dudley [35] sat in Lord Rothschild’s box [36], dressed in pale blue and wearing her splendid turquoise collar, as well as a diamond tiara and necklace with large pendant. Not many boxes away sat the lovely Lady Brooke [37], in white satin with pink sleeves and a diamond belt, as well as tiara and necklace.

The Royal box was filled with Ambassadors, among whom sat the handsome Countess Deym [38] in a splendid tiara. Lord Brooke [37] was in the uniform of the Warwickshire Yeomanry. Lord Curzon [39] had with him Lady Evelyn Curzon [40]. Lady Randolph Churchill’s dark hair [41] was dressed very high, with a diamond star and aigrette just above the brow. Near her sat Mrs. Mackay [42], in white, with diamond and turquoise tiara and necklace. In the next box was Lady Ashburton [43], also in white, wearing enormous emeralds in her diamond necklace. Earl Cadogan [44], with his Garter across his uniform, the Duc d’Orleans [45], the Portuguese Ambassador [46], Count Deym [47], Signor Randegger [48], wearing the Order of the Crown of Italy, Baron Hirsch [49], Count Kinsky [50], in a Hungarian uniform, Lord Rowton [51], in Levee dress, Mr. Hugo Wemyss [52], Col. Stanley Clarke [53], the Hon. Seymour Fortescue [54], in naval uniform, Lord Lonsdale [55], with a full red cloak upon his shoulders, were a few noted among the crowd.

Lady Lonsdale [56], in black, Countess Spencer [57], the Hon. Mary Thesiger [58], in cream lace and diamond tiara, Mrs. Arthur Sassoon [59], Mrs. Bradley Martin [60] with a wonderful tall crown of diamonds, Lady Craven [61], Lady Churchill [62], Mrs. Naylor Leyland [63] in an immense tiara and three or four diamond necklaces, Lady Londesborough [64] in black with sapphires and diamonds, the Marchioness of Londonderry [65], splendidly handsome in white, with diamond tiara, necklace, pendant, and girdle; Lady Skelmersdale [66] in white satin and green sleeves; Lady Feo Sturt [67], in white, with turquoise sleeves; the Marchioness of Ormonde [68], in white, with a collar of pearls and diamond tiara; Mrs. Labouchere [69], in pink and diamonds; Mrs. McEwan [70], in black, with magnificent diamonds; her daughter, Mrs. Ronald Greville [71], in palest blue, with splendid diamonds; Mrs. Ronalds [72], in white, with diamond star-tiara and aigrette; Lady de Grey [73], Countess Cadogan [74], Miss Knollys [75], Mrs. Arthur Paget [76], Lady de Trafford [77], are among those likely to remain in the memory of those who were present.

The white turban of an Indian prince who occupied the box next Lady de Grey was a picturesque item on display. White was in an overwhelming majority of the ladies’ dresses, and so numerous were the diamond tiaras that the eye experienced a sort of relief when it fell on a parure of sapphires, turquoise, emeralds, or rubies.

|

| Nellie Melba, dressed for her role as Ophelia in Hamlet, photographed in 1893 (Swedish Performing Arts Agency/Wikimedia Commons) |

The performance itself demands little more than mere formal notice. It was a happy idea to give a complete work, instead of a programme of excerpts from various operas. “Romeo et Juliette” [78] which was represented in French, was, however, selected with no special reference to the Royal marriage, although the representation last evening terminated with the potion scene, the tragical last act being struck out as being unsuitable to so festive an occasion.

A slight limp betrayed the fact that M. Jean de Reszko’s sprained ankle [79] was not entirely healed; but, as the popular tenor jokingly pointed out, a hero so fond of climbing balconies might sometimes expect to be lame, while it is only the bare truth to state that he was in splendid voice, and acted the part of Romeo with all his old charm. Madame Melba [80], one of the prettiest of Juliettes, and M. Edouard de Reszko [81] an imposing Friar Lawrence, were also members of a cast which in almost every respect was quite familiar to the Covent Garden subscribers.

As is usual upon State occasions, there was little or no applause, but after the balcony scene the Royal party made a rather lengthy entr’acte, and the Prince of Wales called Sir Augustus Harris into the reception room, and personally congratulated him upon organising and carrying out absolutely without a hitch one of the most brilliant entertainments ever given at the opera.

NOTES

1. Prince George, Duke of York (1865-1936), later King George V of the United Kingdom, was second in line to the throne in 1893 following the shocking death of his elder brother, the Duke of Clarence. George had hoped to marry a cousin, Princess Marie of Edinburgh, but she turned him down in favor of the future King of Romania. Instead, he proposed to his late brother’s fiancee, Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, to whom he had become close as they mourned for the late Duke. They married at the Chapel Royal, St. James’s Palace on July 6, 1893, two days after this opera gala.

2. Princess May of Teck (1867-1953), later Queen Mary of the United Kingdom, was a great-granddaughter of King George III. She had been engaged to the eldest son of the Prince and Princess of Wales, the Duke of Clarence, but he died suddenly in January 1892. A year later, in May 1893, she accepted a proposal from his younger brother, the Duke of York, and she was once again on track to become Britain’s future queen consort. Her granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth II, sits on the British throne today.

3. Sir Augustus Henry Glossop Harris (1852-1896), the British actor and operatic theater impresario, was the manager of the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden. Harris was knighted in 1891 by Queen Victoria in honor of his work arranging entertainment during the state visit of her grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, that July.

4. Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (1819-1904) was the uncle of Princess May and a first cousin of Queen Victoria. George was very familiar with Covent Garden; in 1847, he made an illegitimate marriage with the actress Sarah Fairbrother. The couple had three children together. She died in 1890, three years before this performance.

5. Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (1844-1900) and his wife, Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (1853-1920), were Prince George’s uncle and aunt. He’d wanted them to be his parents-in-law, too — he had unsuccessfully courted their daughter, Princess Marie, before her marriage to the Crown Prince of Romania in January 1893. Only weeks after this gathering, Alfred succeeded to a new title, becoming the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on the death of his uncle, Prince Ernst.

6. Prince Francis, Duke of Teck (1837-1900) and his wife, Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge (1833-1897), were Princess May’s parents. Mary Adelaide was a first cousin of Queen Victoria, and although Francis was a member of the extended royal family of Wuerttemberg, the couple and their four children lived in England on the small annuity granted to her by parliament. Princess May’s marriage to the future king helped raise their status and fortunes considerably.

7. Prince Adolphus of Teck (1868-1927), later Duke of Teck and then Marquess of Cambridge, was the eldest son of the Duke and Duchess of Teck and the younger brother of Princess May. Adolphus was a soldier in the British army, and in July 1893, he had recently been promoted to lieutenant. The following year he married Lady Margaret Grosvenor, daughter of the immensely wealthy Duke of Westminster.

8. Prince Francis of Teck (1870-1910), another of Princess May’s brothers, was the second son of the Duke and Duchess of Teck. In 1893, he was serving as a lieutenant in the 1st Royal Dragoons. But his real passion wasn’t the military — it was gambling. He never married, though Princess Maud of Wales (Princess May’s sister-in-law) pursued him before marrying Prince Carl of Denmark in 1896.

9. Prince Alexander of Teck (1874-1957), later Earl of Athlone and the last of the Teck sons, was Princess May’s youngest brother. Ten years after this wedding, Alexander made a royal match of his own, marrying one of Queen Victoria’s granddaughters, Princess Alice of Albany. Alexander was appointed as Governor-General of the Union of South Africa by his new brother-in-law; he also served as Governor-General of Canada during the reign of his nephew, King George VI.

10. Prince Henry of Battenberg (1858-1896) and his wife, Princess Beatrice of the United Kingdom (1857-1944), were Prince George’s uncle and aunt. The couple was raising a young family, including the future Queen Ena of Spain, on the Isle of Wight near her mother, Queen Victoria. Less than three years after this wedding, however, Henry contracted malaria while serving in West Africa as the military secretary to the commander-in-chief of British forces and died.

11. Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (1846-1923), born Princess Helena of the United Kingdom, was Prince George’s aunt. Helena’s marriage to Prince Christian caused family drama and political controversy, but it was happy. She was a very active member of the royal family, championing causes like nursing.

12. Grand Duchess Augusta of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1822-1916), born Princess Augusta of Cambridge, was Princess May’s aunt. She married her first cousin, Hereditary Grand Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, in 1843.

13. Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (1831-1917), a Danish-born German prince, was Prince George’s uncle through his marriage to Princess Helena of the United Kingdom.

14. Grand Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1819-1904) was the sovereign grand duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz for more than four decades. He was Princess May’s uncle through his marriage to Princess Augusta of Cambridge.

15. Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (1850-1942) and his wife, Princess Luise Margarete of Prussia (1860-1917), were Prince George’s uncle and aunt. In 1911, George appointed his uncle to serve as Governor-General of Canada.

16. Alexander Duff, Duke of Fife (1849-1912) and his wife, Princess Louise of Wales (1867-1931), were Prince George’s brother-in-law and sister. At the time of this wedding, Louise had recently given birth to their third child, Maud.

17. The Prince of Wales (1841-1910), later King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, was Prince George’s father. As the eldest son of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, he had been the heir to the throne for his entire life. With his mother ensconced on the Isle of Wight, he and his wife, Alexandra, presided over their own active social circle from their London home, Marlborough House.

18. Queen Louise of Denmark (1817-1898) was Prince George’s maternal grandmother. Born Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel, she had a strong claim to the Danish throne through her mother, Princess Charlotte of Denmark. She consolidated that claim to power when she married another Danish royal heir, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, in 1842. They ascended to the throne in 1863, and several of their children — Frederik, Alexandra, Wilhelm, and Dagmar — reigned over other nations as monarchs and consorts.

19. King Christian IX of Denmark (1818-1906) was Prince George’s maternal grandfather. He became Denmark’s king in 1863, the same year that his eldest daughter, Alexandra, married the heir to the British throne.

20. The Princess of Wales (1844-1925), nee Princess Alexandra of Denmark and later Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, was Prince George’s mother. She focused a great deal of attention — really too much attention — on her children, who called her “Motherdear.”

21. Princess Victoria of Wales (1868-1935), later Princess Victoria of the United Kingdom, was the middle of Prince George’s three younger sisters. Although she was an eligible marriage prospect, especially for foreign princes, Toria never married. Instead, she served as a companion to her mother, Queen Alexandra. George and Toria were close throughout their lives; he was crushed by her death, and he died only a few weeks later. She served as a bridesmaid at this wedding.

22. Princess Maud of Wales (1869-1938), later Queen Maud of Norway, was the youngest of Prince George’s sisters. Bright and funny, Maud cycled through crushes on several royal men (including Princess May’s brother Francis) before accepting a proposal from her Danish first cousin, Prince Carl. When they married in 1896, no one could have guessed that less than a decade later, Carl would be elected the first king of an independent Norway. Carl, who took the name Haakon VII, and Maud were crowned at Trondheim in 1906. Along with her sister, Victoria, she served as a bridesmaid at this wedding.

23. The Tsarevich of Russia (1868-1918), Prince George’s first cousin through their Danish mothers, became Tsar Nicholas II of Russia a year after this royal wedding. He traveled to London to represent his parents, Tsar Alexander III and Tsarina Marie Feodorovna of Russia, at the wedding. He was deeply in love with another of George’s cousins, Princess Alix of Hesse, who was reluctant to marry him because of her devotion to her religion. By the spring of 1894, however, Alix relented. They became Russia’s last imperial couple.

24. Luigi Mancinelli (1848-1921) was an Italian musician, composer, and conductor. He conducted operas at some of the world’s greatest theaters, including the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden and the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, where he was the leading conductor for a decade.

25. Prince Valdemar of Denmark (1858-1939) was Prince George’s uncle. A lifelong sailor, Valdemar married a French princess, Marie of Orleans, in 1885. She was pregnant with their fourth child, Prince Viggo, in July 1893.

26. Prince Albert of Belgium (1875-1934), later King Albert I of the Belgians, was a cousin of Prince George through his grandfather, King Leopold I (who was an uncle of both Prince Albert and Queen Victoria). A teenager at the time of this wedding, Albert inherited the Belgian throne in 1909.

27. Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1844-1921) was a cousin of Prince George; his father, Prince August, was a first cousin of both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Philipp was married to his second cousin, Princess Louise of Belgium, whose sister, Princess Stephanie, married Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria. Philipp and Rudolf were close friends, and Philipp was among the group of men who had discovered the bodies of Rudolf and his mistress, Mary Vetsera, at Mayerling in 1889. Philipp and Louise’s relationship was not a happy one, and they separated three years after this royal wedding, eventually divorcing in 1906.

28. Princess Louise, Marchioness of Lorne (1848-1939), later Duchess of Argyll, was Prince George’s aunt. She was the sixth child of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria. Louise was a talented sculptor and an important patron of the arts in Britain.

29. John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne (1845-1914), later Duke of Argyll, was Prince George’s uncle through his marriage to Princess Louise. He served as Canada’s fourth Governor-General. In 1893, he was serving as Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle.

30. Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar (1823-1902) and his wife, Lady Augusta Gordon-Lennox (1827-1904), were relatives of the British royal family. Edward was a British-born German prince and a nephew of Queen Adelaide, the wife of King William IV of the United Kingdom. He later became a naturalized British subject. His wife, Lady Augusta, was a daughter of the 5th Duke of Richmond. Although their marriage was morganatic, Queen Victoria granted Augusta the right to share her husband’s title, and court documents generally refer to her as “Princess Edward of Saxe-Weimar.”

31. Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh (1876-1936), later Grand Duchess Victoria of Hesse and then Grand Duchess Viktoria Feodorovna of Russia, was a first cousin of Prince George. Queen Victoria helped engineer a match between Victoria Melita (who was known as “Ducky”) and another cousin, Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse. They married in 1894, but the match was a disaster, and they ultimately divorced. Ducky remarried to a maternal first cousin, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia, a union that angered Tsar Nicholas II. She also served as a bridesmaid at this royal wedding.

32. Prince Albert of Schleswig-Holstein (1869-1931) was Prince George’s first cousin. The second son of Prince Christian and Princess Helena, Albert eventually became the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein. He never married, but he did have one acknowledged illegitimate child, a daughter named Valerie Marie.

33. Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein (1870-1948), another of Prince George’s first cousins, served as a bridesmaid at this royal wedding. Helena Victoria, who was known as “Thora” (or, rather unkindly, as “Snipe”), had expressed an interest in marrying George herself. She was discussed in letters exchanged by George and May during their courtship. In the end, Helena Victoria remained unmarried.

34. Prince Louis of Battenberg (1854-1921), later Marquess of Milford Haven, was married to one of Prince George’s first cousins, Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine (1863-1950). Louis had a successful career in the British navy, eventually rising to the rank of First Sea Lord. His children included Lord Mountbatten, Queen Louise of Sweden, and Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, who was the mother of the present Duke of Edinburgh.

35. Georgina, Countess of Dudley (1846-1929), a famous Victorian beauty, was the much-younger second wife of the 1st Earl of Dudley. Georgina was a close friend of the Princess of Wales, and after her husband’s death, she lived in a grace and favor home, Pembroke Lodge, provided by Bertie and Alexandra. She also was one of Bertie’s rumored paramours.

36. Nathaniel Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild (1840-1915) was a wealthy British banker and politician. His friendship with the Prince of Wales dated back to their time as students at Trinity College, Cambridge.

37. Francis Greville, Lord Brooke (1882-1924) and his wife, Daisy Maynard (1861-1938), were part of the Marlborough House set led by the Prince and Princess of Wales. Daisy was one of Bertie’s mistresses (or good friends, depending on who you ask). Less than six months after this wedding, Francis succeeded to his father’s titles, becoming the 5th Earl of Warwick.

38. Countess Anna Deym (1852-1919), nee Countess Anna Schlabrendorf, was the wife of the Austrian ambassador to the Court of St. James. She was partly responsible for a social slight that led to a duel between her husband and Count Francis Lützow, a secretary at the Austrian embassy, in 1891. Lützow wished to bring his new wife into society, and asked if the Deyms would invite her to an embassy function. Because they thought the new Countess Lützow to have questionable character, the Deyms declined. A duel was subsequently fought in Vienna; press reports from the time differ on the weapons used (either pistols or swords), but it doesn’t really matter, as neither party was injured. Following the duel, Countess Deym agreed to receive Countess Lützow, and everyone apparently moved on.

39. Richard Curzon, Viscount Curzon (1861-1929), later 4th Earl Howe, was another member of the Marlborough House set. He eventually served as both Treasurer of the Household and as Queen Alexandra’s Lord Chamberlain. He and his wife, Lady Georgina Spencer-Churchill (daughter of the -7th Duke of Marlborough), had recently celebrated their tenth wedding anniversary.

40. Lady Evelyn Curzon (1862-1913) was Lord Curzon’s younger sister. Three years after this wedding, she married John Eyre.

41. Lady Randolph Churchill (1854-1921), born Jennie Jerome, was the American-born wife of Lord Randolph Churchill and the mother of Sir Winston Churchill. In 1893, her husband, a famous British statesman in his own right, was already suffering from the illness that would eventually kill him. Jennie was a great friend (and maybe also a lover) of the Prince of Wales.

42. Marie Louise Mackay (1843-1921), born Marie Louise Hungerford, was the wife of John William Mackay, an Irishman who was a partner in the “Bonanza firm” that mined the Comstock Lode in Nevada. Mrs. Mackay complained that New York society would not accept her, so her husband bought her a mansion in Paris. She entertained numerous members of high society, including royals, and amassed a truly impressive collection of jewels.

43. Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton (1827-1903), born Louisa Stewart-Mackenzie, was a major Scottish art collector during the Victorian era.

44. George Cadogan, 5th Earl Cadogan (1840-1915) was a Conservative politician; from 1886 until 1892, he had served as Lord Privy Seal.

45. Prince Philippe, Duke of Orleans (1869-1926) was the English-born son of the Count of Paris, the Orleanist claimant of the French throne. The former French royal family lived in English exile in the last half of the nineteenth-century, and Philippe and his siblings moved in royal circles; indeed, his younger sister, Princess Helene, had been deeply in love with Prince George’s elder brother, the late Duke of Clarence. Philippe’s father died in 1894, and he became the French pretender from the Orleanist branch. Philippe was also connected to another non-royal personage mentioned in this article; in the early 1890s, he had an affair with Nellie Melba, who played Juliet in this production.

46. Luís Pinto de Soveral (1851-1922), a Portuguese diplomat, served as his country’s ambassador to the Court of St. James from 1891 until 1895. It makes sense that he’s mentioned in this article just after the Duke of Orleans; Philippe was the brother-in-law of King Carlos I of Portugal.

47. Count Franz Deym (1838-1903), an Austrian diplomat, served as Austria’s ambassador to the Court of St. James from 1888 until his death in 1903. The most infamous moment of his ambassadorial tenure came two years before this wedding, when he fought a duel with one of the secretaries at the embassy. (See Note #38 for more.)

48. Alberto Randegger (1832-1911) was an Italian-born composer, conductor, and voice teacher who spent much of his working life in London.

49. Moritz, Baron von Hirsch (1831-1986) was a wealthy German Jewish financier and philanthropist. He’s probably best remembered to history for his work with helping persecuted Jewish refugees — but he became a close friend of the Prince of Wales largely because of their shared passion for horse racing.

50. Count Karl Kinsky (1858-1919), later 8th Prince Kinsky of Wchinitz and Tettau, was an Austrian prince who moved in aristocratic circles in both London and Vienna. He served as an attaché at the Austrian embassy in London, diplomatically maneuvering Baroness Mary Vetsera and her mother around the city during Crown Prince Rudolf’s visit for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887. Kinsky also won the Grand National in 1883 riding his own horse, Zoedone. He’s probably most famous, though, for his affair with Lady Randolph Churchill.

51. Montagu Corry, 1st Baron Rowton (1838-1903) was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge alongside the Prince of Wales. He famously served as private secretary to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli for fifteen years.

52. Hugo Wemyss (1861-1933), a Scottish diplomat, was a member of Clan Wemyss and a brother of the Laird of Wemyss Castle in Fife.

53. Col. Stanley Clarke (1837-1911), later Sir Stanley Clarke, was a British courtier who was serving as private secretary to the Princess of Wales in 1893.

54. The Hon. Seymour Fortescue (1856-1942) was a British courtier who was serving as an equerry-in-waiting to the Prince of Wales in 1893.

55. Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale (1857-1944) was a British aristocrat who was famous as a sportsman. He was an enthusiastic racing driver, boxer, and fox-hunter. He hosted numerous monarchs at his home, Lowther Castle, for grouse shooting.

56. Grace Lowther, Countess of Lonsdale (1854-1941), born Lady Grace Gordon, was the wife of the 5th Earl of Lonsdale and a daughter of the 10th Marquess of Huntly. Grace was severely injured in a fall while hunting shortly after her marriage in 1878, an accident that killed her unborn child and affected her for the rest of her life.

57. Charlotte Spencer, Countess Spencer (1835-1903), born Charlotte Seymour, was the wife of the 5th Earl Spencer. Her husband was a British courtier and politician; he was serving as First Lord of the Admiralty in 1893.

58. The Hon. Mary Thesiger (1840-1914), daughter of the 1st Baron Chelmsford, was lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Teck.

59. Louise Sassoon (1854-1943), born Eugenie Louise Perugia, was the Italian-born wife of Arthur Sassoon, a wealthy British banker who was a close friend of the Prince of Wales.

60. Cornelia Martin (1843-1920), born Cornelia Sherman, was the wife of Bradley Martin, a wealthy American banker. The Bradley Martins lived most of the year at an estate in Scotland, and their sixteen-year-old daughter, Cornelia, had recently married into the British aristocracy. Four years later, they threw a famously lavish ball in New York in 1897.

61. Cornelia Craven, Countess Craven (1877-1961), born Cornelia Martin, was the daughter of the wealthy American banker Bradley Martin. In April 1893, sixteen-year-old Cornelia married the 4th Earl of Craven, becoming a teenaged countess.

62. Jane Spencer, Baroness Churchill (1826-1900), born Lady Jane Conyngham, was a Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Victoria for nearly half a century. Her death in December 1900 was deeply traumatic for Victoria, who lived only a month longer herself.

63. Jeannie Naylor Leyland (1867-1932), born Jeannie Willson Chamberlain, was the American-born wife of the British politician Herbert Naylor Leyland. Her husband was honored with a baronetcy two years after this wedding. Both Herbert and Jeannie were close friends of the Prince of Wales.

64. Edith Denison, Countess of Londesborough (1838-1915) was the wife of the 1st Earl of Londesborough and a daughter of the 7th Duke of Beaufort. In 1871, the Londesboroughs inadvertently nearly killed the Prince of Wales, when the plumbing at their home near Scarborough failed and gave the heir to the throne typhoid fever. Bertie was near death, but he survived.

65. Theresa Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Marchioness of Londonderry (1856-1919), born Lady Theresa Susey Helen Talbot, was the wife of the 6th Marquess of Londonderry and a daughter of the 19th Earl of Shrewsbury. The Londonderrys were part of the Marlborough House set, and Theresa caused a scandal in the 1880s when she had an affair with the British politician Harry Cust. Through the machinations of another of Cust’s lovers, Lady de Grey, love letters between Cust and Theresa were sent to Theresa’s husband. Although they did not divorce, the Londonderrys essentially maintained completely separate lives afterward. Anita Leslie claims that Lord Londonderry never spoke another word to his wife, apart from “necessary announcements in public,” after discovering her infidelity.

66. Wilma Bootle-Wilbraham, Lady Skelmersdale (1869-1931), later Countess of Lathom, was the wife of the 2nd Earl of Latham and a daughter of the 5th Earl of Radnor. In 1893, her father-in-law, Lord Lathom, had recently ended his second tenure as Lord Chamberlain.

67. Lady Feodorovna Sturt (1864-1934), born Lady Feodorovna Yorke and later Lady Alington, was the wife of the 2nd Baron Alington of Crichel and a daughter of the 5th Earl of Hardwicke. She was a friend of the Prince of Wales.

68. Elizabeth Butler, Marchioness of Ormonde (1856-1928), born Lady Elizabeth Grosvenor, was the wife of the 3rd Marquess of Ormonde and a daughter of the immensely wealthy 1st Duke of Westminster. Her sister, Lady Margaret, later married Princess May’s brother, Prince Adolphus of Teck.

69. Henrietta Labouchere (1841-1910), born Henrietta Hodson, was the wife of the journalist and politician Henry Labouchere. Harriet was a comic actress and theater manager, and she had a long affair (and a daughter) with Labouchere before marrying him in 1887.

70. Helen McEwan (ca. 1835-1906), born Helen Anderson, was the wife of the millionaire brewer and politician William McEwan. The two had a daughter, Margaret, in 1863, but they didn’t marry until 1885, when their daughter was 21.

71. The Hon. Mrs. Ronald Greville (1863-1942), born Margaret McEwan, was the daughter of William McEwan and Helen Anderson. Two years before this wedding, Margaret married the Hon. Ronald Greville, eldest son of the 2nd Baron Greville. She was a close friend of Queen Mary, and she eventually left her massive jewel collection to the Queen Mother.

72. Fanny Ronalds (1839-1916), born Mary Frances Carter, was the American-born companion of the composer Arthur Sullivan. She also maintained friendships with the Prince and Princess of Wales and other members of the Marlborough House set, notably Lady Randolph Churchill.

73. Gwladys Robinson, Lady de Grey (1859-1917), later Marchioness of Ripon, was a daughter of the 11th Earl of Pembroke. She was married to the 4th Earl of Lonsdale until his death, and then to the 2nd Marquess of Ripon. She was a patron of the arts and a good friend of Nellie Melba, who performed in this opera, and Sir Augustus Harris, the conductor and manager (see note #3). She was also responsible for a lasting rift in the Londonderry marriage (see note #65).

74. Beatrix Cadogan, Countess Cadogan (1844-1907), born Lady Beatrix Craven, was the wife of the 5th Earl Cadogan. Her father was the 2nd Earl of Craven.

75. Elizabeth Charlotte Knollys (1835-1930) served as both Lady of the Bedchamber and private secretary to the Princess of Wales (later Queen Alexandra). She notably saved Alexandra from a fire during her lengthy tenure in her service.

76. Minnie Paget (1853-1919), born Mary Stevens, was the American-born daughter of the wealthy hotelier Paran Stevens and the wife of General Sir Arthur Paget.

77. Lady de Trafford (1866-1925), born Violet Franklin, was the wife of the racehorse breeder Sir Humphrey de Trafford, 3rd Bt.

78. Romeo et Juliette by Charles Gounod, and based on the Shakespeare play, was first performed in 1867. It made its debut in London the same year.

79. Jean de Reszke (1850-1925) was a Polish tenor. He made numerous appearances at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden and in command performances for royal events, including galas honoring the Shah of Persia and the Emperor of Germany, as well as Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

80. Nellie Melba (1861-1931), an Australian soprano, was one of the most famous entertainers of her day. She made her debut at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden in 1888, and she sang her final performance there in 1926.

81. Edouard de Reszke (1853-1917), a bass singer, was the younger brother of Jean de Reszke. He performed at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden more than 300 times.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- …

- 58

- Next Page »