|

| Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images |

The Duchess of Marlborough Egg

|

| The Duchess of Marlborough Egg, made by Fabergé in 1902 for Consuelo Vanderbilt (Wikimedia Commons) |

As we wrap up our month-long focus on Russia’s imperial jewels, we’re looking today at an unusual example from Fabergé’s series of incredible bejeweled Easter eggs. While most of the eggs were made for the Romanovs, this particular egg was commissioned by an American — and remained in American hands for a century.

|

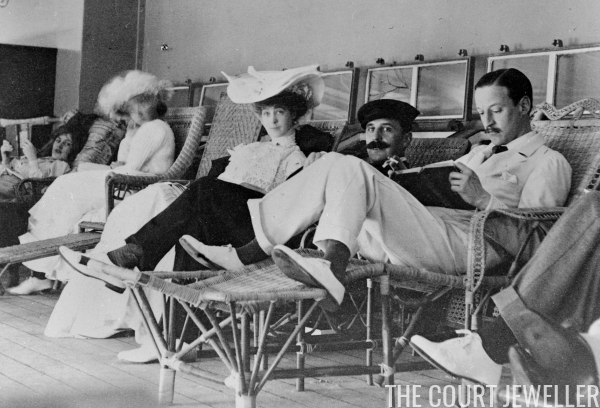

| The Duke and Duchess of Marlborough sailing with companions from France to India ahead of the Delhi Durbar, ca. 1902 (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) |

In January 1902, the 9th Duke of Marlborough and his American-born duchess, Consuelo Vanderbilt, headed to Russia to attend the whirlwind of imperial court occasions held annually during the celebrations of the Orthodox New Year. In her memoirs, Consuelo explained that they decided to go because her “husband, who had a weakness for pageantry, wished to play a fitting part in festivities renowned for their magnificence.” The couple stuffed their luggage with the necessary gowns, uniforms, and jewels, recruited companions and staff (including a private detective to keep an eye on the gems), and headed east for St. Petersburg.

|

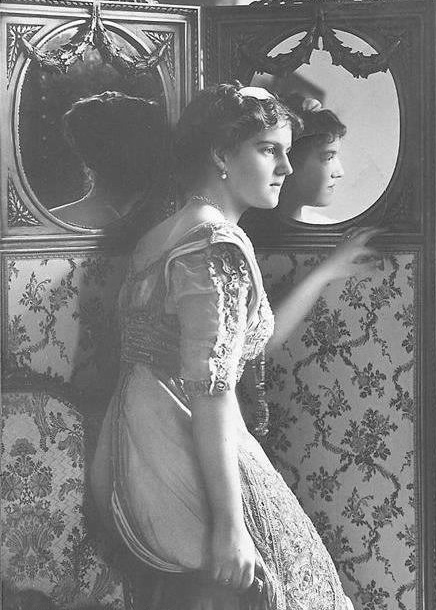

| A famous portrait of Consuelo Vanderbilt during her marriage to the Duke of Marlborough, ca. 1911 (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) |

Consuelo wasn’t overly impressed with Russia on the whole, though she was wowed by the balls held at the imperial palaces and by the incredible jewelry worn by the imperial women. (Grand Duchess Vladimir even took Consuelo on a private tour of her jewels, showing her “endless parures” that were “set out in glass cases in her dressing room.” Can you imagine? Consuelo expressed relief that she’d bought a new, grand turquoise necklace for the trip.) But while she was there, likely during her visit to Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna’s palace, she absolutely fell in love with one feature of Romanov life: the incredible jeweled Easter eggs made for them by Fabergé.

|

| The Duchess of Marlborough Egg (Wikimedia Commons) |

The same year, Consuelo decided that she needed a glittering Fabergé egg of her own. She commissioned the firm to make her a large egg in shades of rose and gold that also functioned as a clock, much like a combination egg/clock she may have seen in Marie Feodorovna’s collection. Consuelo’s clock egg, made of pink and white enamel, gold, rose-cut diamonds, and seed pearls, sits atop a pedestal base that is adorned with love trophies, including torches and arrow, and Consuelo’s monogram, “CM.” A diamond-studded serpent rests on the base of the egg, slithering toward the clock band; its forked tongue indicates the hour. The egg was made by one of the firm’s masters, Mikhail Perkhin, who died the year after the Marlborough egg was made. Consuelo’s egg was the only large Fabergé egg ever commissioned by an American.

|

| Ganna Walska, wearing an outfit that reportedly raised eyebrows, attends the opening night of Lohengrin at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, 14 December 1945 (Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) |

By 1926, Consuelo’s life had changed radically. Separated in 1906, she and Marlborough had divorced in 1921. Later that same year, she married a French aviator, Jacques Balsan, and settled in Paris. In the summer of 1926, Consuelo was focused on raising funds to build a new hospital in Vincennes. A charity gift auction was held as part of that fundraising effort, and Consuelo writes that she donated “a Fabergé clock [she] had brought back from Russia” to the auction. The buyer was another woman with American connections: Ganna Walska, the Polish-born wife of Harold Fowler McCormick, son of the founder of International Harvester.

|

| A view of the love trophies adorning the base of the Duchess of Marlborough Egg (Wikimedia Commons) |

In Walska, the egg found another eccentric, fascinating owner. An aspiring opera singer — even though her voice was reportedly mediocre at best — Walska’s career was heavily promoted by McCormick and his fortune. (Orson Welles apparently used their relationship as one of the inspirations for the film Citizen Kane.) McCormick and Walska divorced in 1931, five years after she acquired the Marlborough egg. In 1965, long after her divorce from her last (and sixth!) husband, Walska also decided to sell the egg. She needed funds to continue improvements to Lotusland, her private estate in Santa Barbara, California. The property is now a botanical garden and can be visited by the public.

|

| Detail of the serpent’s tail portion of the Duchess of Marlborough Egg (Wikimedia Commons) |

A New York auction house, Parke-Bernet, handled the sale. They advertised the egg as an “important wrought gold, rose, and white enamel serpent and egg rotary clock, set with diamonds.” Intriguingly, the lot notes for the 1965 auction tried to link the Marlborough egg with royalty, noting, “We believe the monogram to be that of Queen Alexandra, wife of Edward VII. By curious coincidence, the date beneath the clock, 1902, was the year of their coronation and could possibly have been a royal gift. She was an admirer of Fabergé’s work, and her collection is now at Sandringham.” Of course, we know this is not true; the egg belonged to a member of the aristocracy (Consuelo), not royalty.

|

| Malcolm Forbes and close friend Elizabeth Taylor at the Château de Balleroy in Normandy, 11 June 1988 (MYCHELE DANIAU/AFP/Getty Images) |

It’s tough to know how much this incorrectly-advertised royal provenance affected the sale of the egg, but one thing is for certain: through the Parke-Bernet sale, the egg became the cornerstone of one of the most important American collections of Fabergé ever assembled. On May 15, 1965, the egg was purchased by Malcolm Forbes, the famous American entrepreneur and magazine publisher. He paid $50,000 for the ornament. It was the first Fabergé egg that he bought; over time, he assembled a collection that reportedly included as many as twelve eggs.

|

| The Duchess of Marlborough Egg (Wikimedia Commons) |

After Forbes’s death in 1990, the collection stayed together for more than a decade. But in 2004, just before the collection was set to go on the auction block at Sotheby’s, nine eggs, including the Marlborough egg, were purchased privately from the Forbes family by the Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg. (The Bay Tree Egg, which we discussed earlier this month, was also part of the collection sold to Vekselberg.) The Marlborough egg and the rest of the Fabergé eggs owned by Vekselberg now reside in his private Fabergé museum in St. Petersburg. Intriguingly, although it was made in Russia by a Russian firm, the 2004 purchase marked the first time that the Marlborough egg was owned by a Russian national.

Jewel History: Russian Duchess Hid Jewels in Bottles (1931)

|

| A portrait of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna taken by Jaeger during her marriage to Prince Wilhelm of Sweden, 1912 (Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons) |

LONDON — One of the few members of the Russian royal family who have lived to tell the tale is the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna [1], a first cousin of the Tsar [2]. Therefore, her book, “Things I Remember,” [3] dedicated to her murdered father, the Grand Duke Paul [4], and published recently, is a valuable document.

|

| Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna in Russian court dress, including a kokoshnik with pearl embellishments (Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons) |

The Grand Duchess, who was born in 1890, felt from the first the insecurity of the Romanov dynasty, perhaps because her mother, Princess Alexandra of Greece [5], was half a Dane. She was brought up almost wholly by two English nurses, so that she was six years of age before she could speak a word of Russian.

|

| A portrait of Maria Pavlovna during her Swedish royal marriage, ca. 1911 (Grand Ladies Site) |

Among her most curious experiences under the revolutionary regime is the manner in which she hid her jewels [6]. She placed her diamonds in an empty bottle, first poured paraffin over them and then ink. Other jewels were fastened to paper-weights or dipped in wax so that, provided with a wick, they appeared to be the ends of large church candles.

|

| Maria Pavlovna poses wearing the emeralds she received from her aunt, Grand Duchess Ella (Wikimedia Commons) |

Her husband — for she had married Sergius Putiakin [7], whose father had been governor of the royal palace at Tsarskoye Selo [8] — was forced to clean the streets, and in order to make money she took up ikon painting and coloring wooden Easter eggs.

|

| Maria Pavlovna wears pearls in exile, ca. 1921 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Her experiences in escaping with her husband and his brother to the part of the Ukraine in the hands of the Germans were nerve-shaking. She had some important documents in a piece of soap and her money in a penholder, and only by great audacity managed to get through the Bolshevik barrier to the German lines, ultimately escaping to Romania [9].

NOTES

1. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia (1890-1958), a granddaughter of Emperor Alexander II, was a member of the Russian imperial family (by birth) and Swedish royal family (through her first marriage). She lived through the tumultuous years of the Russian Revolution and spent much of her adult life in exile. During World War I, she worked as a nurse. After she fled Russia, she worked as a fashion designer, a photographer, an artist, and a writer. She is often called Maria Pavlovna “the Younger” to distinguish her from the other famous Maria Pavlovna in the family: Grand Duchess Vladimir.

2. Emperor Nicholas II of Russia (1868-1918), the last Russian tsar, was one of Maria Pavlovna’s first cousins; their fathers, Emperor Alexander III and Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia, were brothers. Maria Pavlovna died almost sixty years ago, but she still has first cousins living today, including the Duke of Edinburgh. (Her mother, Princess Alexandra, and his father, Prince Andrea, were siblings.)

3. Maria Pavlovna wrote a pair of memoirs, Things I Remember (1930), which was titled Education of a Princess in American editions, and A Princess in Exile (1932).

4. Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia (1860-1919), the youngest child of Emperor Alexander II and Empress Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, was Maria Pavlovna’s father. He married a Greek princess, Alexandra, but after her death in childbirth, he fell in love with Olga Valerianovna von Pistohlkors, the wife of Grand Duke Vladimir’s aide-de-camp. After she began an affair with Paul, Olga and her husband divorced, but Paul’s nephew, Emperor Nicholas II, refused to allow Paul and Olga to marry; when they married morganatically anyway in 1902, Nicholas ordered them to leave Russia. Paul’s two children, Maria Pavlovna and Dmitri Pavlovich, were sent to live with their uncle and aunt, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich and Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, in Moscow. After a decade in exile, Nicholas pardoned Paul and rescinded his banishment, giving Olga the title of Princess Paley. But Paul and Olga’s return to Russia eventually proved to be his downfall. In 1919, he was murdered by the Bolsheviks.

5. Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark (1870-1891), Maria Pavlovna’s mother, was the eldest daughter of King George I and Queen Olga of the Hellenes. Through her mother, Alexandra was a great-granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia. In 1889, Alexandra married a Russian cousin, Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich. They had a happy, passionate marriage, but Alexandra’s health was precarious. She died after giving birth prematurely to her second child, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, in 1891.

6. Maria Pavlovna’s jewels nearly jeopardized her life during the revolution. She was in Moscow on a trip with her second husband, Sergei, to retrieve her jewelry from a bank vault when the October Revolution of 1917 suddenly broke out. They left the jewels behind and fled back to the home they shared in St. Petersburg (then called Petrograd) with Sergei’s parents. Her in-laws were the ones who eventually managed to retrieve her jewels, and she subsequently smuggled some of them out of Russia via Sweden.

7. Prince Sergei Mikhailovich Putyatin (1893-1966), the son of the commandant of Tsarskoye Selo, was Maria Pavlovna’s second husband. They married in 1917 and had one child together, a son who died just after his first birthday. They divorced in 1923.

Maria Pavlovna’s first husband had had a royal pedigree of his own. Prince Wilhelm of Sweden (1884-1965) was the second son of King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria of Sweden. Encouraged by her aunt and guardian, Grand Duchess Ella, Maria accepted a proposal from Wilhelm in 1907, and the couple married at Tsarskoye Selo in the spring of 1908. They had one son, Prince Lennart, but the marriage was unhappy. Maria’s cousin, Emperor Nicholas II, officially dissolved the marriage in 1914. Maria returned to Russia, but Prince Lennart remained behind in Sweden to be raised by his father’s family.

8. Tsarskoye Selo, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was the country home of the Russian imperial family. The estate’s name roughly translates as “the Tsar’s village.” Peter the Great presented the site to his wife, Catherine I, in 1708, and the Romanovs occupied it for the next two centuries, building various palaces, schools, and churches there.

9. Maria Pavolvna’s exile began with her flight into the Ukraine in 1918. The document smuggled inside that piece of soap was a Swedish diplomatic paper identifying her as a former princess and the mother of a Swedish princess. From there, she stayed with a cousin, Queen Marie, in Romania. A peripatetic life followed; she lived in Britain, France, America, Argentina, and Germany, where she died in 1958.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- …

- 58

- Next Page »