Sunday’s airing of Victoria on Masterpiece was a two-parter, and today, we’re recapping the jewels and the history of the second episode shown, “The Sins of the Father.” (Catch up on our previous recaps over here!)

We begin with the birth of Albert and Victoria’s second child, Albert Edward, who will one day become King Edward VII. That means that it’s November 9, 1841.

Albert announces to the officials waiting outside that they have a Prince of Wales. Not quite yet, Albert — the title of Prince of Wales isn’t automatic. When Bertie was born, he was automatically Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay. Victoria didn’t make her son Prince of Wales until a few weeks later, on December 8, 1841, when he was just about one month old.

Albert is enamored with his son. Victoria is less so; famously uninterested in babies, she declares that they all “look like frogs to her.” She’s feeling melancholy after having the baby, and she can’t explain why. (Postpartum depression wasn’t really a recognized thing in the 1840s.)

In Coburg, Albert’s randy old dad, Ernst Sr., cavorts with his mistresses. He’s rather seriously cavorting with one of them, in fact, when he up and dies.

The show makes it look as if Albert’s father departed just as his son was born, but that wasn’t the case. Ernst Sr. died in January 1844. By that time, Albert and Victoria had three children (Vicky, Bertie, and Alice), and Victoria was in the early months of her pregnancy with their fourth child, Alfred.

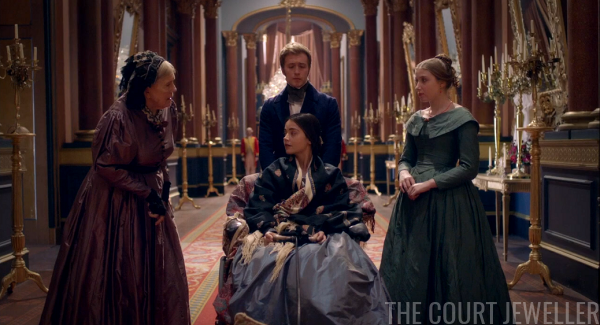

Victoria’s back in her pushchair, listening listlessly to Charlotte Buccleuch express horror about a lady wearing diamonds in the daytime. (Step off, Charlotte!) Victoria says they don’t need to worry about inappropriate diamonds at court, because she’s not ready to go out in public anytime soon.

Her melancholy intensifies, to the point that she’s sadly playing the piano alone wearing no jewelry at all. Albert comes in and sings along in German, but that doesn’t even make her smile. He’s worried.

The Duchess of Kent admires her new grandson, but Victoria is pretty much off in her own world.

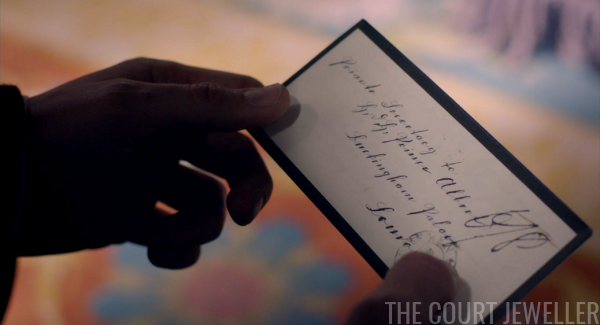

And then the bad news arrives for Albert from Coburg. He knows it’s not good even before he opens the envelope, because the paper is edged in black. Victoria is finally shaken out of her own depression just a little because of her sympathy for her grieving husband.

The real Albert and Victoria learned of his father’s death on February 3, 1844, via an express that had arrived at 4 AM from King Louis-Philippe of the French, not from relatives in Coburg. (Louis-Philippe’s daughter, Louise, was married to King Leopold of the Belgians, the late Duke’s brother.) The Observer commented, “It is considered as a most extraordinary circumstance, that no direct information relative to this important event should have been received from Germany.” The Coburg court chamberlain did arrive in England shortly afterward to convey the news in person.

Albert tells Lehzen that he’s heading straight to the funeral in Coburg. While he’s gone, he wants her to solve the mystery that’s plaguing the palace: which staff member blabbed to the press about the recent break-in by a boy. He warns her that if they don’t find the mole, every staff member will be fired — including her. (Spoiler: the blabber is a relative of Victoria’s head dresser. Albert decides to let the dresser stay.)

The real Albert, though, didn’t attend his father’s funeral; it took place only about two days after Albert learned of his father’s death. He did go to Germany to see his family after his father’s death, but he didn’t make the trip until the beginning of April 1844.

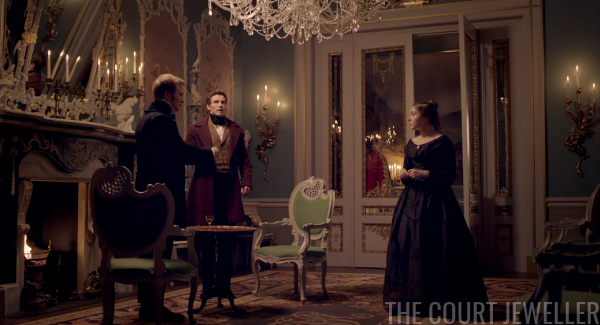

Victoria finally tracks down Albert and tries to comfort him. She wants to go to Coburg, too — he says she shouldn’t. She points out that they’ve never spent a night apart, which was true. She didn’t go with him to Coburg during the Easter 1844 trip after his father’s death, and it was the first time he and Victoria had been apart since their wedding.

Victoria, who has a teeny bit of sparkle on the neckline of her gown, watches with Lehzen as Albert departs. While no one traveled to Germany for Ernst Sr.’s funeral in real life, the British court went into full mourning.

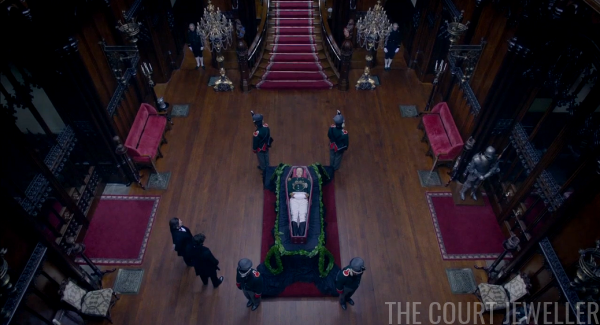

In Coburg, Albert joins Ernst Jr. to view their father’s body lying in state. A ducal coronet rests on Ernst Sr.’s body, which seems like an interesting choice on the part of the production.

Uncle Leopold shows up to mourn his brother, too.

Back at Buckingham Palace, everyone’s in mourning clothes. Victoria, Charlotte, and Wilhelmina sit in the nursery, sketching the children. Victoria’s irritable, and she’s angry that little Vicky won’t sit still. (In the same scene, Charlotte makes reference to her “late husband.” The 5th Duke of Buccleuch didn’t die until 1884!)

Albert’s beating himself up, feeling guilty about his final interactions with his father. When Ernst tells him precisely how the old duke died, Albert stops feeling quite so bad. “He died doing what he loved,” Ernst says languidly. (Ernst would know. By the way: by 1844, Ernst had a wife, Princess Alexandrine.)

In London, Peel tries to convince Victoria that she should attend the opening of the new Thames Tunnel, one of the projects of famed Victorian innovator Isambard Kingdom Brunel. She resists, but Drummond has brought a visual aide: a model of the tunnel. It intrigues Victoria, but she still says she won’t attend. (The tunnel opened to the public in March 1843.)

Victoire can’t figure out why her daughter is so upset, and she can’t figure out why she isn’t spending all her time with her babies.

In Coburg, the ducal coronet rests atop the coffin at Ernst Sr.’s funeral. There are no women present anywhere in these scenes — not Ernst Jr.’s wife (who hasn’t yet appeared on the show), and definitely not Ernst Sr.’s second wife, Marie of Württemberg, who was also his niece (blech).

After the funeral, Albert gazes at a miniature of his mother — Ernst Sr.’s first wife, Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. (That’s a real portrait of her.) Albert’s parents were both unfaithful, and they divorced when Albert and his brother were children. She was only 30 when she died of cancer.

Uncle Leopold finds Albert and talks with him about Louise. Albert’s still angry at the idea that his mother would leave her children behind, fitting right in with the episode’s discussions of the “right” kind of mothering. Leopold explains that it was more complicated than that. And then he drops a big old bomb: after his first wife, Princess Charlotte, died in 1817, and Ernst Jr. was born in 1818, Leopold and Louise “comforted each other.” Without really saying it, he implies that he’s Albert’s real father.

Okay, so I know what you’re all thinking — could this possibly have been true? It’s a fact that there were rumors about Albert’s true paternity even during his lifetime. Because his mother had one documented affair, which reportedly occurred after his birth, Albert was dogged by suggestions that he was the product of another extramarital liaison. (The complicated medical history of the family also raises questions about Albert’s parenthood.) A biography published in the 1970s argues that Leopold could indeed have been Albert’s father. The truth is that we’ll probably never really know.

Back in England, Victoria sneaks up to the nursery in her nightgown to look in on the baby. She spies on him through the slightly-open door, but she can’t make herself go inside.

The next day in Coburg, Ernst (who is now the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha) and Albert make family small talk at a gathering. They discuss “Cousin Ferdinand,” whom Uncle Leopold wants to marry off to the Queen of Spain. (I believe they’re referencing Prince Ferdinand, the son of their Uncle Ferdinand, who eventually married Queen Maria II of Portugal and was proclaimed King Ferdinand II of that country.)

Albert expresses surprise that Leopold hasn’t tried to marry Ernst off yet. (Just for fun, let’s suspend disbelief for a second and pretend that Ernst hadn’t already been married for two years by the time his father died. Go ahead, show, let’s see what you’ve got.)

Leopold’s candidate for Ernst, Princess Alda of Oldenburg is a) fictional, and b) a pain in the backside. (Oh, show.) She arrives and immediately begins complaining. Her lady-in-waiting, though, is wearing a ferronniere — maybe she’s more Ernst’s type?

She may be severe and humorless, and she may be imaginary, but at least she’s wearing earrings and a brooch!

In England, Peel arrives with some bad news for Victoria: there’s been an explosion in the armory at the Tower of London, and five men have died. (This really happened in October 1841, about a week before the birth of the Prince of Wales. We are all over the map in this episode.) She wants to send condolences, but he urges her to appear in person.

She finally relents, struggling to decide what accessories to wear. With a cameo pinned to her dress, she admits that she’s nervous.

She sucks it up and goes, and it does make a difference to the people.

Even Charlotte Buccleuch is impressed. She’s the only one who directly ties Victoria’s “low spirits” to the birth of baby Bertie — she has been where Victoria is, and she understands. Charlotte experienced something similar with the birth of her daughter Mary — who wasn’t born until 1851, because this show is so, so strange in its approach to its source material.

Meanwhile, Lord Alfred and Drummond have found a little quiet time for flirtation over drinks — but then they’re unceremoniously uninterrupted by Wilhelmina, who has lost her Chopin. Such timing.

Later, Alfred finds out that Drummond’s engaged to be married, and his fiancee is an aristocrat, the daughter of the Marquess of Lothian. Alfred offers begrudging congratulations.

Back at the palace, Alfred and Wilhelmina take part on a very Victorian courtship ritual: playing glasses. She’s still mopey about Ernst, and he’s mopey about Drummond, so obviously, the answer is to be mopey together. (They’re holding hands openly by the end of the scene, which is an interesting choice for the time!)

In Coburg, Albert is still so distressed about Leopold’s big revelation that goes to a tavern to track down Ernst. Albert! In a bar! Ernst is kind of amused and maybe a little concerned, but they end up drinking in tribute to their late father.

Albert gets sloshed, which is what any sane Victorian prince would do if he learned that his father might have been a king rather than a duke, right? He says he feels like he “has elves around [his] person.” Okay, dude. He tries to tell Ernst about Leopold’s paternity bombshell, but Ernst talks over him.

He’s still so wasted when he gets back to Rosenau in the morning that he tries to put on a suit of armor. Leopold finds him and scolds him for his drunken state.

Albert unloads on him, telling him that his entire life is now a lie, and Victoria is married to a bastard. Leopold warns him that no one else should find out — especially not Victoria.

Albert heads for home, telling Ernst to come visit him in England ASAP.

Back in England, things are looking up for Victoria. She even has a new puppy!

When Albert gets home, he and Victoria are kind of awkward with each other, but a new puppy always helps break the ice.

Soon enough, they’re comfortable with each other again.

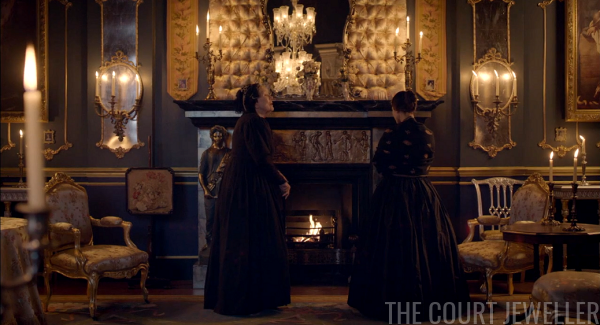

But after his trip, it’s Albert’s turn to be depressed. Victoria wants him to come with her to the tunnel opening, but he declines.

She can tell something’s not right, but he isn’t talking.

So she goes on her own, meeting Brunel at the tunnel while wearing the production’s little version of the Albert Brooch.

At home, she’s even getting more comfortable in the nursery.

But Albert’s still in a funk. Victoria finally talks to him about the children, and how she sometimes feels like an imposter, both as a mother and as a queen. He’s glad she’s finally been honest with him.