|

| ODD ANDERSEN/AFP via Getty Images |

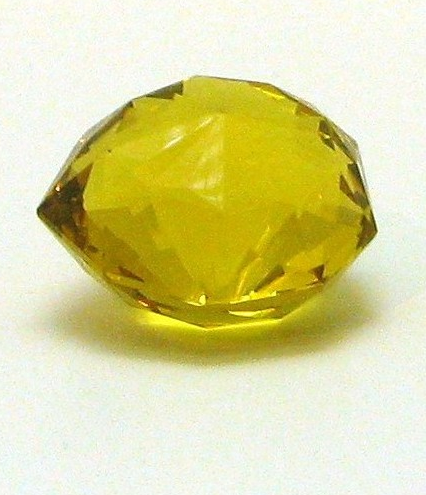

The Florentine Diamond

|

| Copy of the Florentine Diamond (Wikimedia Commons) |

Some famous diamonds are set in pieces of jewelry, while others reside in museums. And then there are the really fascinating gems that have been stolen, lost, or otherwise disappeared into the mists of time. Today’s gem, the Florentine Diamond, belongs to that roster of gone-but-not-forgotten stones.

|

| Illustrated detail of the facets of the Florentine Diamond, ca. 1907 (Wikimedia Commons) |

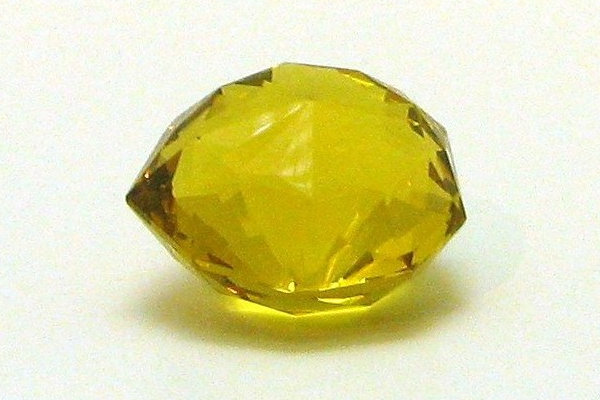

The accounts of the earliest centuries of the diamond’s post-discovery existence are, as is true with so many of these stones, a little more lore and legend than history. Most everyone seems to agree that the diamond was mined in India. It somehow made its way to Europe, but we don’t really seem to know for certain whether that path involved transaction, theft, or a combination of the two.

One version of the story connects the canary-colored diamond with the Portuguese colonial history of India. In that story, the diamond was “acquired” by the colonial governor of Goa from one of the Kings of Vijayanagara (perhaps King Sriranga I?) in the late 1500s. The story goes that the Portuguese official handed off the diamond to the Jesuits, who were conveniently running an inquisition (!) in Goa at the time. They supposedly took the diamond to Rome, bringing it into the European world for the first time, where it was purchased by Ferdinando de Medici (1549-1609).

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Charles the Bold, ca. 1618 (Wikimedia Commons) |

But that’s just one version of the story. Another version of the diamond’s history finds it first in Bruges in the middle of the 15th century. There, it was supposedly transformed from a rough stone into the famous 137.27-carat faceted diamond by Lodewyk van Bercken, an innovative Flemish diamond cutter. His patron, Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1433-1477), had commissioned him to cut the diamond. Charles supposedly brought the diamond with him to the battlefield — not a great move! — and during a battle in the 1470s, he lost it. The story goes that it was picked up by a lowly soldier, who didn’t know the value of the yellow stone and sold it for a pittance. From there, it allegedly hopped from Switzerland to Genoa to Germany to Florence, maybe even making a quick stop at the Vatican.

|

| Ferdinando II de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (Wikimedia Commons) |

One thing is for certain: by 1657, the Florentine Diamond was in the possession of Ferdinando II de Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. He showed the diamond to Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, the French famous jewel merchant and world traveler. (You’ll probably recognize Tavernier’s name from his association with the famous Hope Diamond.) Tavernier wrote about the diamond in his memoirs, giving us one of the first documented references to the gem. The Medicis kept the diamond through their long tenure as rulers of Florence and Tuscany. When the last Medici grand duke died without an heir in 1737, he was succeeded by his second cousin, the Duke of Lorraine — who also became the new owner of the Florentine Diamond.

|

| Empress Maria Theresa painted by Martin van Meytens, 1759 (Wikimedia Commons) |

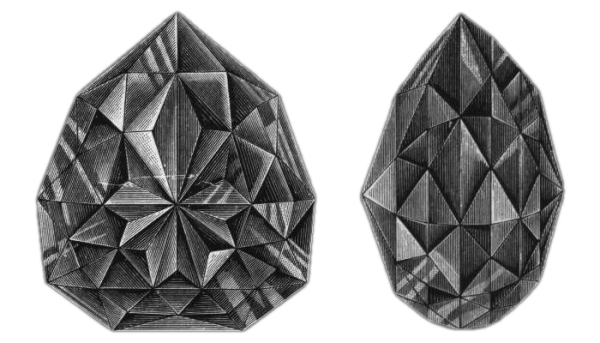

The Duke of Lorraine is better known to history as the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I. His wife, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria-Hungary (and lots of other places, including Milan and Parma), wielded the real power behind the scenes of their titles. (You might recognize them as the parents of Marie Antoinette.) Their marriage brought the diamond into the Habsburg imperial treasury, where it stayed for almost two centuries.

|

| The Florentine Diamond set in a cap ornament, ca. late 19th century (Wikimedia Commons) |

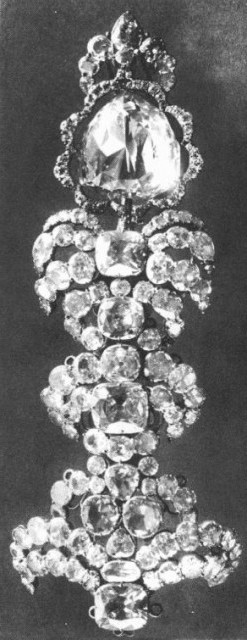

In 1833, the New York Mirror published a travelogue from American writer Nathaniel Parker Willis that included a visit to the imperial treasury in Vienna. He described the Florentine as “a lump of light.” Willis wrote that even though “enormous diamonds surround it … it hangs among them like Hesperus among the stars.” The Habsburgs used and displayed the diamond in various ways, placing it in a crown, brooches, and a cap ornament (pictured above).

|

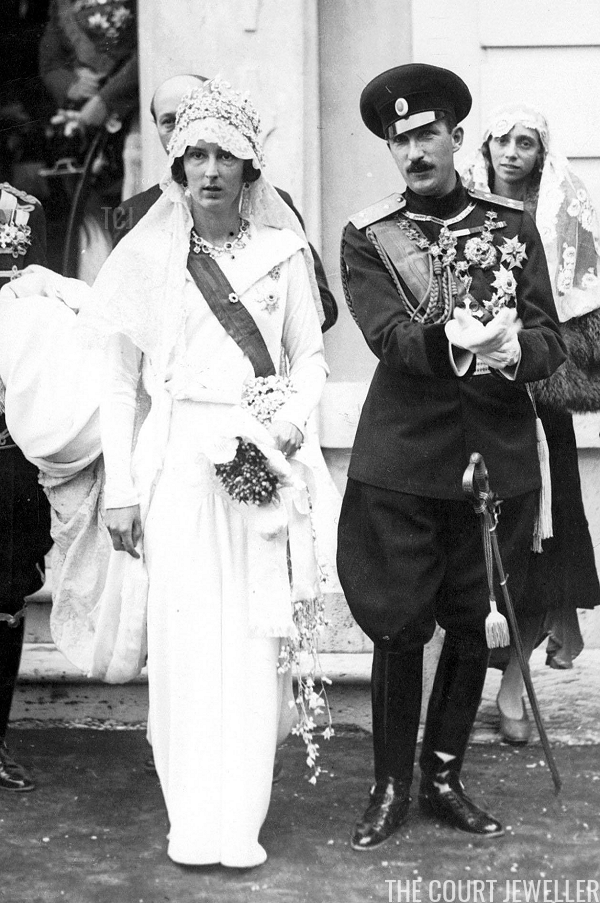

| Emperor Karl and Empress Zita, ca. 1911 (Wikimedia Commons) |

By 1918, world war had ravaged Europe, and the Habsburgs were toppled from their imperial throne. The last imperial couple, Emperor Karl I and Empress Zita, fled with their family to Switzerland. Controversially, they took many of the crown jewels along with them, including the Florentine Diamond. Some Austrians maintained that these jewels were the property of the state, and Karl had no right to abscond with them. And then, to make things even more complicated, the Italians also filed a claim over the Florentine Diamond, arguing that the diamond had been willed by the Medicis to the people of Florence in the eighteenth century.

|

| Karl, Zita, and seven of their children, ca. 1921 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The diamond vanished completely from public view. Some believe that it was stolen from the imperial family in exile, while others believed that the Habsburgs stashed the diamond in a Swiss bank and used it as collateral for substantial loans. In 1921, the London Observer‘s correspondent in Geneva wrote that the crown jewels taken by Karl “are still in this country, so far as is known; and it is on these jewels that he must have received pecuniary advances.” Matters were complicated yet again when Karl died in April 1922, leaving Zita with eight children and little security or stability. Sensational press reports claimed that “the Florentine Diamond was the last barrier standing between the ex-empress and actual poverty.” And she certainly needed the money, as her widowhood lasted for 76 years (!) until her death in 1989.

|

| Copy of the Florentine Diamond from the Museum Reich der Kristalle in Munich (Wikimedia Commons) |

So what happened to the diamond next? I wish we had an answer to that question! There are rumors that it made its way to South America, or even to the United States. But in reality, there’s been no substantiated appearance of the Florentine Diamond in more than a century. The bright golden “diamond” shown above is actually a copy of the Florentine from a Munich museum. It’s quite possibly the closest thing most of us will ever come to seeing the genuine article.

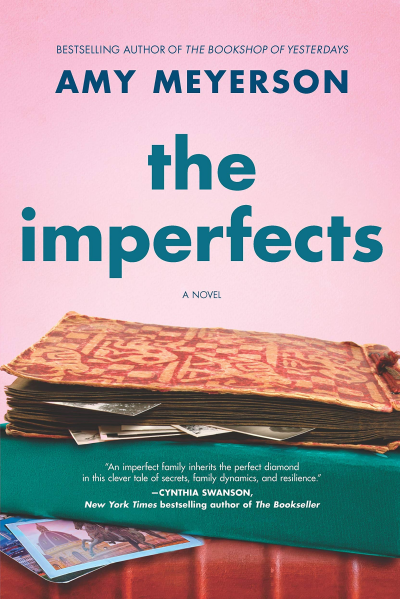

But if you’re interested in fictional endings to this diamond mystery, let me again recommend Amy Meyerson’s new novel, The Imperfects. We talked about this briefly in my May recommendations post. The book follows the story of a contemporary American family, the Millers, who discover that the enormous gemstone they’ve secretly inherited from their grandmother is, in fact, the missing Florentine Diamond. What would you do if you inherited such a spectacular treasure? You can find out what the fictional Millers decide to do in Meyerson’s excellent book.

And if you’re interested in learning even more about The Imperfects, I’ll be chatting all about it virtually with Amy this evening! (I have lots of questions to ask her about the inspiration behind the jewel mystery in the book!) You can join us live online for the event, which is sponsored by the Cecil County Public Library. Click here to register for a link to join in tonight at 6:30 PM Eastern Time!

The Bulgarian Fleur-de-Lis Tiara

|

| Princess Marie Louise of Bulgaria wears the Bulgarian Fleur-de-Lis Tiara (Wikimedia Commons) |

Royal families often own tiaras that are full of symbols related to their countries and dynasties. Today’s sparkler, the fascinating Bulgarian Fleur-de-Lis Tiara, is a particularly interesting example.

|

| Prince Ferdinand and Princess Marie Louise photographed in Austria, ca. 1893 (Wikimedia Commons) |

In 1887, Bulgaria’s National Assembly was searching for a new sovereign. The previous ruling prince, Alexander of Battenberg (brother of Prince Henry and Prince Louis, who both married into the extended British royal family), had abdicated a year earlier following a military coup. The assembly found its new prince in Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was a well-connected royal, with family ties to the British, Portuguese, and Belgian royal families. He was also a grandson of King Louis Philippe I, who had reigned in France from 1830 to 1848.

Ferdinand was formally elected as the next Prince of Bulgaria in July 1887. His ascension was greeted with shock by many of his fellow European sovereigns; Queen Victoria wrote that he was “unfit” for the role and “should be stopped at once.” Regardless, he had a much longer tenure as sovereign than his predecessor. Soon, he was on the hunt for a royal bride to help him secure the line of succession. This wasn’t an easy task. One British newspaper reported that it was “well known” that Ferdinand had “proposed to half the eligible princesses of Europe,” and had “failed in all his numerous matrimonial ventures in England, Bavaria, Austria, and Belgium.”

Ferdinand’s mother, Princess Clementine, worked for years on negotiations with Robert, Duke of Parma, hoping to arrange a marriage for Ferdinand with Robert’s eldest daughter, Princess Marie Louise of Bourbon-Parma. (Robert had a total of twenty-four children; Marie Louise’s siblings included Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary and Prince Felix of Luxembourg.) After several years, Clementine finally succeeded, and the engagement between Marie Louise and Ferdinand was officially announced in February 1893.

|

| Princess Marie Louise, ca. 1893 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Prince Ferdinand and Princess Marie Louise met for the first time during their engagement celebrations at the bride’s family home, Schwarzau Castle, in Austria. (Marie Louise’s stepmother, Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal, was the sister of Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria. She was the sister-in-law of Emperor Franz Josef I.) They married in a Catholic ceremony in the chapel of the Duke of Parma’s Italian villa in April 1893.

The Bulgarian people celebrated the arrival of their new princess with a special national gift: a tiara featuring the country’s national colors, presented on behalf of the women of the nation. The diamond, emerald, and ruby tiara, with its distinctive fleur-de-lis designs, was made by Köchert, the Viennese firm that became famous as court jeweler of the Austrian imperial court. (The fleur-de-lis tiara is sometimes confused with the small crown, or coronet, that was given to Marie Louise by her groom; that crown, also made by Köchert, features fleur-de-lis elements in its design and was set with diamonds, emeralds, rubies, and sapphires.)

|

| Princess Marie Louise, ca. 1893 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Contemporary newspaper reports described the fleur-de-lis tiara as “a superb diadem” that would undoubtedly become “the most conspicuous ornament among the Bulgarian crown jewels.” One paper noted that the tiara was made of “five magnificent clusters of diamonds in the shape of the Bourbon lily. The base of the diadem is made of rubies, emeralds and diamonds, representing the Bulgarian colors — red, white, and green. On the central lily is a ruby of rare brilliancy and value.” Marie Louise often wore the fleur-de-lis tiara with other ruby and diamond jewels from her collection. In this impressive bejeweled portrait, the princess wears the tiara with her ruby and diamond festoon necklace, as well as a ruby and diamond negligee-style pendant brooch.

|

| Philip de Laszlo’s portrait of Princess Marie Louise, ca. 1894 (Wikimedia Commons) |

In de Laszlo’s famous portrait of Princess Marie Louise, he depicts her wearing the tiara with the ruby negligee brooch pinned at her neck, plus a diamond and emerald cluster brooch on the bodice of her gown. Her wrists are adorned with more diamond and emerald bracelets.

Although the marriage between Ferdinand and Marie Louise was not a love match, the couple had four children together. Their eldest son, Prince Boris, was born nine months after their wedding. In 1899, twenty-nine-year-old Marie Louise died after giving birth to their fourth child, Princess Nadezhda.

|

| Boris and Giovanna pictured in Assisi at their wedding luncheon, October 1930 (Scherl/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy) |

Three decades passed before the tiara was worn in public again. Ferdinand — who was upgraded to the title of tsar in 1908 — passed the throne to his elder son, Boris III, at the end of World War I. In 1930, Boris married Princess Giovanna of Italy, the fourth child of King Vittorio Emanuele I and Queen Elena. Boris had been baptized Catholic but converted as a small child to the Eastern Orthodox faith. His marriage to an Italian Catholic princess was a complicated matter. It took several months of diplomatic negotiations between the families, the governments, and both churches before the engagement could officially be announced by the bride’s parents in October 1930. The couple were pelted with rain and hail when they arrived for their Catholic wedding ceremony at the Basilica of St Francis of Assisi on October 25.

|

| Giovanna wearing the tiara at her wedding luncheon in Assisi, October 1930 (Scherl/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy) |

Giovanna did not wear a tiara for the Italian wedding ceremony, choosing instead to anchor her lace veil with a garland of flowers. Afterward, however, she added the Köchert fleur-de-lis tiara to her ensemble for the wedding luncheon that followed at Villa Constanzi in Assisi. The photo above shows the tiara on the new queen (or tsaritsa) at the lunch celebrations; you’ll note that she’s also wearing Princess Marie Louise’s ruby and diamond festoon necklace. She wore the tiara again a few days later, when the couple was married again in an orthodox ceremony at the Alexander Nevsky Church in Sofia. Giovanna subsequently took on the Bulgarian version of her name, becoming known as “Tsaritsa Ioanna.”

Boris and Ioanna had two children, Princess Marie Louise and Prince Simeon, both born before the outbreak of World War II. (Bulgaria and its royal family occupied complicated political territory during the war. In 1943, after a meeting with officials in Berlin, Boris suddenly (and mysteriously) died. He was succeeded by six-year-old Simeon, whose uncle, Prince Kyril, served as regent.

|

| Simeon and Margarita on their wedding day in Switzerland, January 1962 (screencapture) |

Simeon II of Bulgaria is one of the most interesting royal figures of the past century. After becoming a monarch as a young child, Simeon’s life went through another upheaval when he was seven. The Soviets invaded Bulgaria, executing Prince Kyril and sending Simeon, his mother, and his sister into house arrest. In 1946, the Bulgarian monarchy was officially abolished by a referendum, and the family went into exile. They fled to Egypt, where Ioanna’s father, the deposed Italian King Vittorio Emanuele, was living. He was educated there until the family was granted asylum by General Franco and allowed to move to Spain. Throughout their life in exile, however, the family managed to hold on to a good deal of their jewelry.

In Spain, Simeon met his future wife: Margarita Gómez-Acebo y Cejuela, daughter of the Marquess of Cortina. Unfortunately, she was especially equipped to understand Simeon’s traumatic childhood, as her parents had been executed during the Spanish civil war. Like Simeon, she had been displaced during the war, living with various relatives in France and Spain. The couple celebrated their marriage with a pair of ceremonies — a civil wedding and an orthodox ceremony — in Lausanne in January 1962. For the religious ceremony, pictured above, Margarita wore the Köchert fleur-de-lis tiara with a tulle veil. The tiara was also worn by Simeon’s sister, Princess Marie Louise, for her wedding to Prince Karl of Leiningen in 1957.

|

| Simeon, pictured in France during his tenure as Bulgaria’s prime minister, November 2006 (STEPHANE DE SAKUTIN/AFP via Getty Images) |

Simeon and Margarita raised a large family in Spain, and all five of their children — Kardam (who died in 2015), Kyril, Kubrat, Konstantin-Assen, and Kalina — married Spaniards. The family maintains close ties with the Spanish royal family. At the end of the Communist era, Simeon returned to Bulgaria, where his public life took yet another fascinating term. In 2001, he was elected as Prime Minister of Bulgaria, serving in the role for the next eight years.

|

| Simeon and Margarita at Buckingham Palace, May 2012 (Chris Jackson/Getty Images) |

Though Simeon and Margarita have found a home again in Bulgaria, we haven’t seen the tiara in more than half a century. There’s been loads of speculation about where it is — whether the family still owns it, or if it’s been broken up, or even sold. The word on the street is that the family does still own the tiara, but that it is extremely fragile and unable to be worn. If that’s true, I’d love to see this one restored and brought out for us to see and enjoy once more!

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- …

- 48

- Next Page »