|

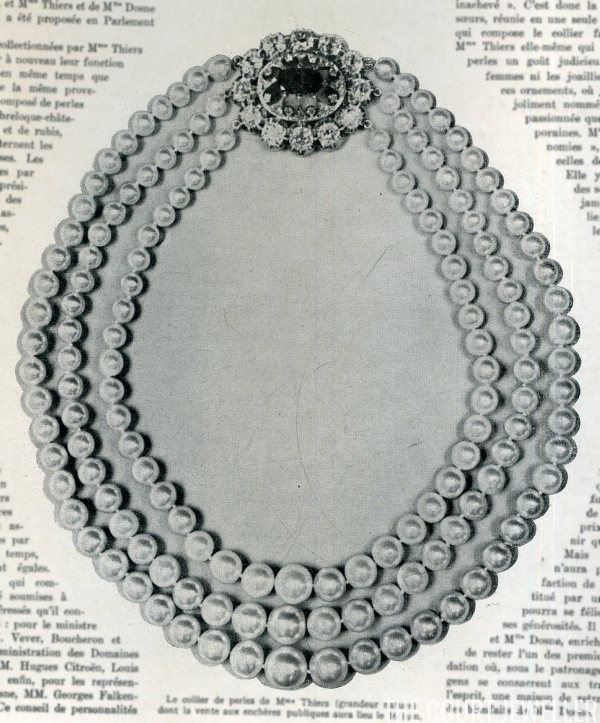

| Elise Thiers’s pearl necklace, ca. 1924 (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

The wonderful pearl necklace which belonged to Mme. Thiers, wife of the distinguished French diplomat [1], and which was left to the French nation by her and placed in the Louvre, is dying from the mysterious, obscure disease which attacks these gems. The necklace is composed of three strands, made up of one hundred and fifty of the finest pearls ever brought up from the depths. When Mme. Thiers gave the necklace to the French people, it was worth fifty thousand pounds. There are few jewellers who would give £5,000 for it now, so far has the malady progressed.

Experts are at a loss to explain just what it is that makes pearls stricken and die. Apparently it is a form of starvation. It seems as though the gem feeds upon the life in the delicate skin of women. That is why, jewellers say, pearls should always be worn next to the flesh [2].

|

| Elise Thiers (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

By the terms of Mme. Thiers’s gift, her necklace cannot be taken from its case in the Louvre [3]. If it could be lent to some woman the French government could trust, the experts believe that the majority of the pearls would recover. This is impossible, and so the necklace is to die. Day by day, the globes are darkening, becoming ugly, old, and withered.

The malady of pearls has been known for ages to the more subtle minds of the East. It is only recently that the West has come to recognise that the phenomenon exists. There are some women who cannot wear pearls, whatever it is about women to which pearls are sensitive is inimical to the gems. For the same reason, there are some women who cannot wear turquoises. The most brilliant blue turquoise will speedily turn a dark and soapy green. There are some women on whom an opal will sparkle with all the beauty of its fettered fires, and the very same opal worn upon another woman will be lifeless as a piece of clay.

|

| Queen Mary, resplendent in pearls, including the pearl-topped Girls of Great Britain and Ireland Tiara (Photo: Grand Ladies Site) |

The great jewellers now recognise this peculiarity and keep in reserve women upon whom the pearl thrives. Some grand duchess or some great society lady will find that her pearls are becoming lustreless; she will take them to her jeweller, and for one or two months one of the friendly women will wear next her to her skin many thousands of pounds worth of gems, and then the pearls are returned shining, vivid with life and perfect once again [4].

Pearls are also often rejuvenated by being sunk in sea water. The Queen [5] is passionately fond of pearls. Her collection is more valuable than any in the world. She has a crown and enormous ropes and buckles of them. When she is in what is known as her pearl regalia, the gems on her are worth four hundred thousand pounds. It is probable that two hundred thousand pounds more would not cover the value of those she does not wear.

Not long ago, one of her necklaces showed signs of discoloration and the characteristic illness. It was taken to the jeweller, who secretly immersed it in the sea. Guards watched it night and day for three months. Then the pearls were brought up and found to be perfectly restored.

|

| A youthful Sisi wearing pearls (Image: Grand Ladies Site) |

It seems incredible that there is any actual life in these products of an oyster, and yet pearls are mysterious things. Legends crowd around them. Men dare dishonour and death for them, and women, throughout the ages, have dared dishonour and death for them, too. It seems incredible that there is life in them, and yet a thing that feeds, becomes ill, recovers, and changes with its wearer is approaching in its nature very near to what we term life.

It is a historical fact that when the late Empress Elisabeth of Austria was seized with typhoid fever, her great pearl necklace immediately began to fade [6]. It was sunk in the Adriatic Sea and guarded by a government ship. The pearls lie there to this day, and are taken up once a year and examined. Gem experts say it will be years before their colour is restored.

NOTES

1. Elise Thiers (1818-1880) was the wife of Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877), the first president of the third French Republic. Her relationship with her husband was definitely unconventional and definitely scandalous; she was the daughter of one of his previous mistresses. The Thiers family was unpopular with France’s aristocracy, many of whom considered them to be nouveau riche social climbers. In 1880, Elise bequeathed her husband’s art collection (and her pearl necklace, which was comprised of pearls bought individually from Bapst) to the Louvre, who reluctantly accepted, although the quality of the collection was not considered to be really up to the Louvre’s standards. (It was too “bourgeois,” of course.)

2. Pearls contain small amounts of water, and when they’re not worn (or when they’re stored in a dry place), they can dehydrate. Contact with the human body is thought to help the pearls absorb the moisture they need to retain their luster. (Of course, perspiration and oil from the skin can also damage pearls, so it’s apparently a fine line.)

3. Well — sort of. According to Hans Nadelhoffer’s Cartier, the Louvre decided that the Thiers collection (including the necklace) lacked the aethestic and educational value required to keep it in the museum’s holdings. In 1924, the museum sold the necklace to Cartier. The jewelry firm displayed the necklace for years, but it seems likely that they eventually sold it (or dismantled it) as well.

4. Queen Ingrid of Denmark reportedly wore some of the family’s heirloom pearls at night while she slept to help restore their luster and brightness.

5. The “Queen” in question seems probably to be Queen Mary, but the description of the “pearl regalia” could surely also apply to Queen Alexandra’s wedding gift parure.

6. In another version of this story, Elisabeth’s pearls go gray and lifeless after she hears about the death of her son, Crown Prince Rudolf. In this rendition, the pearls were supposed to have been dunked in the Ionian Sea off the island of Corfu to help revive them.