|

| Wikimedia Commons |

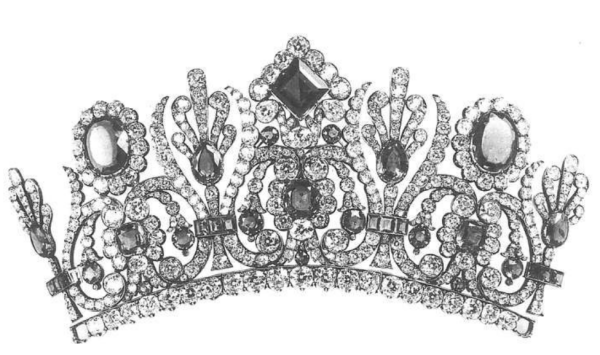

So far, museum week has brought us tiaras linked to Empress Josephine of France and her successor, Empress Marie Louise. Today, we’ve got a look at a tiara that also belonged to a very important French royal woman from the same era: the diamond and emerald tiara that belonged to the Duchess of Angoulême.

|

| The French royal family, painted ca. 1782 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The title “Duchess of Angoulême” might not immediately ring a bell for you, but I bet this woman’s other title, “Madame Royale,” just might. Princess Marie-Thérèse Charlotte of France was the first child of King Louis XVI and his Austrian-born queen, Marie Antoinette. Her birth in 1778, eight years after her parents’ marriage, led to much rejoicing at the French court. She was given the title of “Madame Royale,” traditionally bestowed on the eldest daughter of French kings, at birth. She was followed by two younger brothers and a younger sister, and with the succession secure, the future of the Bourbons in France seemed bright.

But, as well all know, revolution was brewing. The political situation in France grew tenser and tenser. Two of the royal children died, first little Princess Sophie in 1787, and then the small Dauphin, who died only a month before the storming of the Bastille in the summer of 1789. Madame Royale was only twelve years old when the family made a thwarted attempt to escape from Versailles. In the summer of 1792, they were imprisoned, and a few months later, her father was executed.

|

| Madame Royale, painted by Heinrich Füger after her release from prison, ca. 1796 (Wikimedia Commons) |

In prison, the teenager’s family was slowly peeled away from her one by one. First her brother, who was now recognized by royalists as King Louis XVII, was taken away to be imprisoned separately. (After suffering from years of neglect, he died in 1795.) Next, her mother, Marie Antoinette, was taken away to a separate cell, where she stayed for a few months before her own execution in October 1793. And then, Madame Royale’s final companion, her aunt Elisabeth, was taken away and executed, too.

The young princess, now the only surviving member of her immediate family, was totally isolated from any remaining extended family members, and she stayed that way for years, imprisoned with only a single female companion to keep her company. She knew that her father was dead, but she maintained hope that she would see her mother and brother again—until the summer of 1795, when she was finally told the truth about what had happened to the rest of her family.

|

| The Count of Provence, who became King Louis XVIII in 1814 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Two of Madame Royale’s uncles had managed to escape France. The Count and Countess of Provence had successfully fled to the Netherlands on the same night that the royal family had been detained in their attempt to escape Versailles in 1791. His younger brother, the Count of Artois, had left France with his wife and children three days after the storming of the Bastille in 1789, encouraged to take refuge elsewhere by King Louis XVI.

Now that both Louis XVI and Louis XVII were dead, the Count of Provence found himself at the head of the family. He proclaimed himself King Louis XVIII in 1795. Though she was the only surviving child of Louis XVI, Madame Royale wasn’t in line to inherit the throne herself, thanks to France’s adherence to Salic succession laws. But the new king knew that his niece was an important part of the succession puzzle, and he was keen to keep her as a part of the royal line.

In the autumn of 1795, Louis entered negotiations to have Madame Royale released from her confinement. That December, on the night before her seventeenth birthday, she was finally freed as part of a prisoner exchange. She was taken to the imperial court in Vienna, where her cousin, Emperor Francis II, was on the throne. While in Austria, she would have become well acquainted with Francis’s daughter, Marie Louise (who became Empress of France as Napoleon’s second wife in 1810).

|

| The Duke of Angoulême, ca. 1796 (Wikimedia Commons) |

King Louis was keen to get his niece into his custody. Finding a place to set up a shadow royal court proved challenging, but ultimately Tsar Paul I of Russia offered Louis the use of Jelgava Palace in present-day Latvia. Madame Royale joined her uncle and aunt at the castle in 1799. Once she had arrived, Louis put his plan to secure the family succession in place. He told her that he had a final message for her from her parents. Their greatest wish, he told her, was that she would marry her cousin, Prince Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême. Four years Marie-Thérèse’s senior, Louis Antoine was the elder son of the younger brother of Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, the Count of Artois. Eager to honor her parents, Madame Royale quickly agreed to the marriage.

It was all a ruse. Neither Louis XVI nor Marie Antoinette had ever expressed a desire for their daughter to marry the young duke. But Louis XVIII was in a hurry to secure the royal succession, and he’d probably have said anything to convince his niece to help him. Though Louis had been married to Princess Marie Joséphine of Savoy since 1771, the couple had no children. The next in line to the throne was his brother, the Count of Artois, and after him, the Duke of Angoulême. The Count of Artois wasn’t happy about the marriage plans, but Louis XVIII pressed on anyway. Louis wasn’t just trying to appease royalists and capitalize on sentiment and popularity by keeping Madame Royale in the main line of the family; he was also trying to engineer the future of the monarchy itself.

We don’t know whether Madame Royale knew that her uncle had deceived her. She followed through with the planned marriage either way. Louis Antoine and Marie-Thérèse were married at Jelgava Palace on June 10, 1799. For the next fifteen years, the Duke and Duchess of Angoulême were part of a roaming royal court. While Napoleon sat on the throne in France, they moved around Europe, seeking refuge in the various countries that were battling against Napoleon’s imperial armies. (Tsar Alexander I of Russia’s changeability on this matter presented a particular problem for their stability.) Eventually, the court found a home in England, where they rented a country house, Hartwell House in Buckinghamshire, from Sir Charles Lee. Louis XVIII’s wife, Marie Joséphine, died on the estate in 1810, making Marie-Thérèse the highest-ranking woman in the family.

|

| François Gérard’s portrait of King Louis XVIII of France in his state robes, ca. 1814 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The fortunes for the family suddenly turned in the spring of 1814. After a failed attempt to invade Russia, Napoleon’s army was on a downward spiral. Paris surrendered in March, leading to Napoleon’s abdication and exile in April. The Bourbons were restored to the throne in his wake, with the family arriving triumphantly in Paris in May. (On the way, the family participated in a grand procession through the streets of London, with King Louis XVIII and the Prince Regent riding together in the lead carriage.) Marie-Thérèse was returning to Paris for the first time since her liberation almost twenty years earlier, and it’s said that she fainted when she caught sight of the Tuileries Palace, where she had been imprisoned for so many years.

The restoration of the monarchy wasn’t an easy period for the Duchess of Angoulême. Constantly on guard, she understandably found it difficult to trust the people who surrounded her. She was frequently called upon to assess the claims of various men who fraudulently purported to be the late Dauphin, arguing that her brother hadn’t really died in 1795. And one of her most serious and important tasks was securing a proper burial for the remains of her parents and brother. All three were reburied at the Basilica of Saint-Denis in January 1815.

And then—to top it all off—a month later, Napoleon escaped from his exile in Elba and returned to try to reclaim the throne once more. As his army approached Paris, the royals fled once more, this time seeking refuge in Belgium. Marie-Thérèse, though, wasn’t with them. She had been in Bordeaux when Napoleon had arrived on French soil, and she rallied local troops behind her. Ultimately, she decided to leave when she realized that her actions could cause civil war and strife in the city. Napoleon reportedly quipped that she was “the only man in her family” when he heard about her attempt to stay and fight.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

It only took 110 days for coalition forces to oust Napoleon for a second time, with a decisive defeat at the Battle of Waterloo leading him into a second exile, this time on the island of St. Helena. King Louis XVIII and his family returned to Paris once more. The press reported on the triumphant journey made by the Duke and Duchess of Angoulême as they processed from Bordeaux to Paris, receiving a reception “bordering on adoration” according to one newspaper.

With the threat of Napoleon gone, the Bourbons were able to settle more confidently back on to the throne of France. As the Duchess was the senior woman at court, stepping into the place once occupied by her mother, she needed plenty of jewels to wear for grand state occasions. She also had access to the crown jewel collection. In 1819, a cache of fourteen emeralds from the crown jewels was used to construct a brand-new tiara for the duchess. The tiara, which features diamond scroll elements hugging the green stones, was made by jewelers from Maison Bapst, the firm that served as the court jeweler to the Bourbons during this period.

|

| Portrait of the Duchess of Angoulême by Alexandre-François Caminade, ca. 1827 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Marie-Thérèse, Madame Royale and Duchess of Angoulême, capably served as France’s first lady during her uncle’s reign. But she was not able to do the one thing that her uncle had so desperately wanted: produce an heir to the throne. Though newspapers often speculated over the course of her marriage about the possibility that she might be pregnant, Marie-Thérèse never gave birth to a child. She was 35 when the Bourbons were restored to the throne, and years of imprisonment, exile, and tragedy certainly must have taken a toll on her body.

With the succession hanging in the balance, the family turned to the Duke of Angoulême’s younger brother, the Duke of Berry, to secure the Bourbon dynasty. In 1816, he married Princess Caroline of Naples and Sicily, forging an alliance with two Italian kingdoms in the process. The marriage produced four children, with two surviving to adulthood. But for a brief moment in 1820, it looked as if the hopes of a Bourbon heir were dashed completely.

The Duke and Duchess of Berry had a five-month-old daughter, Mademoiselle d’Artois. (The Duchess of Angouleme was one of her godmothers.) Two previous children had died in infancy. On February 13, 1820, the royal couple left their baby behind at the palace and went to the opera. As they walked to their carriage after the Académie Royale de Musique after the performance, a man, Louis Pierre Louvel, stepped toward the couple and stabbed the duke. Louvel was a Bonapartist supporter who despised the Bourbons. He wanted to bring about the end of the royal dynasty, and by murdering the duke, he almost succeeded. With no male heir, the Bourbon throne would eventually pass to the Orleans branch of the family. The French legislature debated making changes to the law of succession to allow the Duchess of Angoulême to become queen regnant. For the Duchess of Angoulême herself, though, her brother-in-law’s death was one more reminder of the mortal peril that awaited the royal family seemingly at every turn in Paris. One contemporary news article described her profound reaction to the murder: “The Duchess d’Angoulême was so penetrated with profound grief, that she never shed a tear.”

|

| Portrait of the French royal family by Antoine Jean-Baptiste Thomas, ca. 1823 |

It must have felt like a miracle when the family discovered that the widowed Duchess of Berry was expecting a child—and even more like a miracle when, seven months after the death of her husband, she gave birth to a boy. The baby, who was most often referred to by the title of Count of Chambord, features prominently in royal artwork from the period. The painting above, completed by Antoine Jean-Baptiste Thomas in 1823, was commissioned by the Duchess of Angoulême herself. It shows the duchess standing on the left beside her husband, who holds the hand of King Louis XVIII. Behind the king stands the Count of Artois, holding the young Count of Chambord, while the Duchess of Berry stands to the right with Mademoiselle d’Artois, who clutches the arm of the king. The Duchess of Angoulême, clad in the jewels of a French queen, gestures toward the baby, as if to say, “Look! We have an heir to the throne after all.”

|

| François Gérard’s portrait of King Charles X of France in his state robes, ca. 1825 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Bourbons had an heir, but after the death of King Louis XVIII in 1824, they very quickly had no throne to sit on. The Duchess of Angoulême’s father-in-law succeeded to the throne as King Charles X, but his conservative and regressive policies made him almost immediately unpopular. The July Revolution toppled him from the throne in August 1830. At the Château de Rambouillet, Charles X signed his abdication papers, after which his son would also abdicate in favor of the young Count of Chambord. But the Duke of Angoulême wasn’t prepared to follow the plan, and it took twenty minutes for him to be convinced to sign the papers, too. Because of these, there was a brief, twenty-minute interval during which the Duchess of Angoulême actually was Queen of France. (Charles X wanted his cousin, Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans, to recognize the young Count of Chambord as king. Instead, Louis Philippe claimed the throne for himself, reigning from 1830 until 1848.)

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

The Duchess of Angoulême packed her bags and prepared to once again head for a life in exile. We know that she brought some of her personal jewels with her when she left France. But, intriguingly, she decided to leave her diamond and emerald tiara behind in the royal vaults. She reasoned that the tiara was made using emeralds that had come from the crown jewel collection, which meant that it wasn’t really hers, but instead was meant to be worn by a French queen or princess. Given the trauma she suffered as a member of the French royal family—the murders of her parents, brother, and brother-in-law, her own imprisonment, multiple years in perilous exile, and two revolutions—she also may simply have decided that anything to do with the French crown was best left to other people.

|

| Detail of Winterhalter’s portrait of Queen Marie Amelie, ca. 1842 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The next French queen was Louis Philippe’s wife, Marie Amelie of of Naples and Sicily. She was a first cousin of the Duchess of Angoulême; her mother was a sister of Marie Antoinette. (She was also an aunt of the Duchess of Berry. These families were very intertwined.) Marie Amelie seemed destined to become Queen of France one way or another. As a child, she was betrothed to the Duchess of Angoulême’s brother, the Dauphin Louis Joseph, until his death in 1789. Although Marie Amelie had lovely jewels in her own jewelry box, the couple did not embrace the grand trappings of state. They made the decision to live simply and put an emphasis on their family life, hosting few grand galas. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons that Marie Amelie was never depicted wearing her cousin’s emerald tiara. (In some of the only grand portraits of her, she wears her own diamond and sapphire parure.)

|

| Winterhalter’s portrait of Empress Eugenie of France, ca. 1864 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Louis Philippe abdicated following the revolution of 1848, and the monarchy was abolished. But, in nineteenth-century France, there was always a member of a competing dynasty lurking around the next corner. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon and son of Hortense de Beauharnais, was elected president of the new republic in 1848—and, three years later, declared himself president for life. (In an interesting juxtaposition of historical events, the exiled Duchess of Angoulême died only a few weeks before he made himself prince-president.) He made it official in 1852, declaring himself Emperor Napoleon III. During his eighteen-year reign, his wife, Empress Eugenie, was fond of the Angoulême Emerald Tiara, apparently especially liking the way that it looked in her red hair.

|

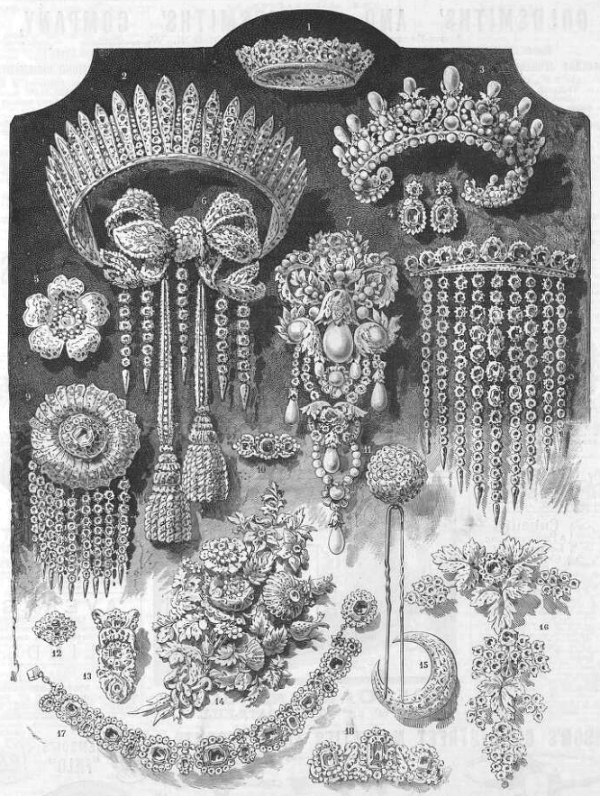

| An illustration featuring some of the pieces of the French crown jewel collection, published in the Illustrated London News at the time of the sale in 1887 |

Eventually, Napoleon and Eugenie were toppled from the French throne, too. When they went into exile in 1870, Eugenie followed the example of the Duchess of Angoulême, taking only her personal jewels with her and leaving the pieces from the crown collection behind. But while that may seem like the safer choice where the status of the jewels was concerned, the Third French Republic’s plans ultimately put the tiara in major jeopardy. At first, the republic merely put the crown jewels on public display. The emerald tiara was showcased at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1878, and then it was exhibited at the Louvre.

Perhaps the government of the republic feared that the presence of the jewels, even in a museum-style display, would tempt one of the pretenders to press their claim. (“Without a crown, no need for a king,” one legislator reportedly said.) Perhaps they simply felt that the jewels were relics of a past they didn’t care to think about repeating, and that they’d be better off with money instead of jewels. Perhaps they had no idea how much money they could make on exhibits of these pieces a hundred plus years later! Whatever the reason, the government decided in 1887 to sell the French crown jewels entirely, mounting a major auction to dispose of the glittering trappings of state. The jewels, including the emerald tiara, were sold, and the collection was scattered.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

The emerald tiara was purchased by an unknown buyer, and it ended up across the Channel in Britain. Eventually, it came into the hands of Wartski, a firm of antique dealers, and subsequently was displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The anonymous owner of the tiara decided to sell the piece, and this time, the people of France reclaimed a piece of their history. The emerald tiara was acquired for the Louvre Museum.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

It seems fitting that one of the main royal jewels to survive from the Bourbon restoration of the 1810s would be the Duchess of Angouleme’s emerald tiara. Today, the tiara is back in the Louvre once more, on display in the grand gallery of jewels and ornaments. It stands as a testament to an era of immense upheaval and a life of great strength amid enormous uncertainty. During her English exile in the early 1800s, a Swedish astrologer offered this description of Madame Royale: “Always near a throne, yet doomed never to ascend it. The daughter of kings, yet much more truly the daughter of misfortune.” In many ways, his statements are accurate, but they also fail to capture the fortitude and character of the princess. Perhaps her emerald tiara, sparkling quietly alone in the Louvre, is a much better representation and remembrance.

Have you visited this important emerald tiara at the Louvre?