|

| Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia, wears the Imperial Crown in an illustration from the time of his 1896 coronation (Wikimedia Commons) |

On this date in 1918, Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna, and Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich were murdered in Ekaterinburg by members of the Bolshevik secret police. In the century that has elapsed since their deaths, the Romanovs have become figures of myth and legend, spectral representations of a glamorous, glittering imperial past. The reality of their lives is much, much more complicated — as is true of the story of any family that exists in the center of power. Today, we’re looking at one of the most important symbols of that power: the Grand Imperial Crown of Russia.

|

| Engraving of the Imperial Crown (Wikimedia Commons) |

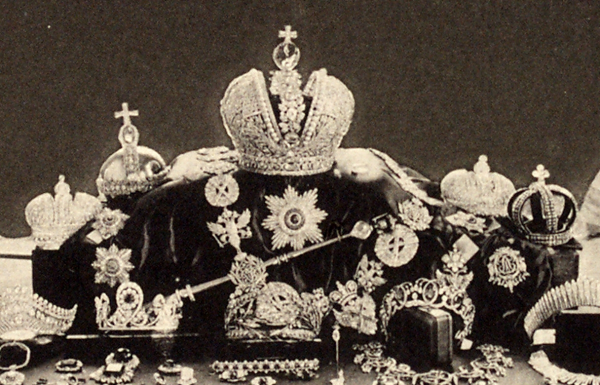

The imposing crown is studded with an incredible 4,936 diamonds. The entire piece is made to resemble a mitre, the traditional headwear of leaders in some religious traditions. The crown consists of two hemispheres (apparently representing the two halves of the Roman empire), which are edged with 75 white pearls and divided by an elaborate central arch. You’ll note oak leaves and acorns in the garland design of the arch, motifs that represent strength and resilience. Atop the arch sits an enormous spinel, which weighs nearly 400 carats and has been part of the imperial collection since the seventeenth century. The diamond cross situated atop the spinel emphasizes the religious role of the monarch. A red velvet cap sits inside the crown.

|

| Detail, Catherine the Great in her Coronation Robes by Vigilius Eriksen, ca. 1778-79 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The first person to wear the crown wasn’t just any monarch — it was none other than Catherine the Great herself. Only a few days after she ascended the throne — following the assassination of her husband, part of a coup she helped engineer — Empress Catherine II commissioned her court jeweler, Jérémie Pauzié, to melt down jewels in the royal treasury that didn’t suit current tastes. The resulting materials were used to make a new crown ahead of her coronation. In his memoir, Pauzié called the crown “one of the richest objects” that “ever existed in Europe.”

|

| Detail, Portrait of Paul I in Coronation Robes by Vladimir Borovikovsky, ca. 1800 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Clearly Pauzié’s design was inspired, because subsequent Romanov monarchs saw no need to change anything about the crown. After Catherine, the crown was worn by every single Russian emperor at his coronation: Paul I (son of Catherine II) in April 1797; Alexander I (son of Paul I) in September 1801; Nicholas I (brother of Alexander I) in September 1826; Alexander II (son of Nicholas I) in September 1856; Alexander III (son of Alexander II) in May 1883; and Nicholas II (son of Alexander III) in May 1896.

|

| Detail, Portrait of Alexander III of Russia by Aleksandr Petrovich Sokolov, ca. 1883 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The coronation of Russian monarchs took place in Moscow, and, appropriately, the imperial regalia was kept in the Kremlin Armory. The actual crowning and anointing took place in the Cathedral of the Dormition, which is also part of the Kremlin complex. Although the religious leaders of the Orthodox Church were central to the coronation ceremony, Russian monarchs crowned themselves. After the prelate handed the crown to the emperor, he placed it on his own head, a gesture that was intended to signal that his imperial power came directly from God.

|

| Illustration of the crowning of Empress Marie Feodorovna from Alexander III’s coronation album (Wikimedia Commons) |

The emperor wasn’t the only person who wore the Imperial Crown. After his crowning, he removed the crown from his own head and placed it briefly on the head of his wife, the new empress consort. She didn’t wear it for long, though. The emperor quickly placed it back on his own head, setting the smaller consort’s crown on hers.

|

| Detail, Coronation of Nicholas II by Laurits Tuxen, ca. 1898 |

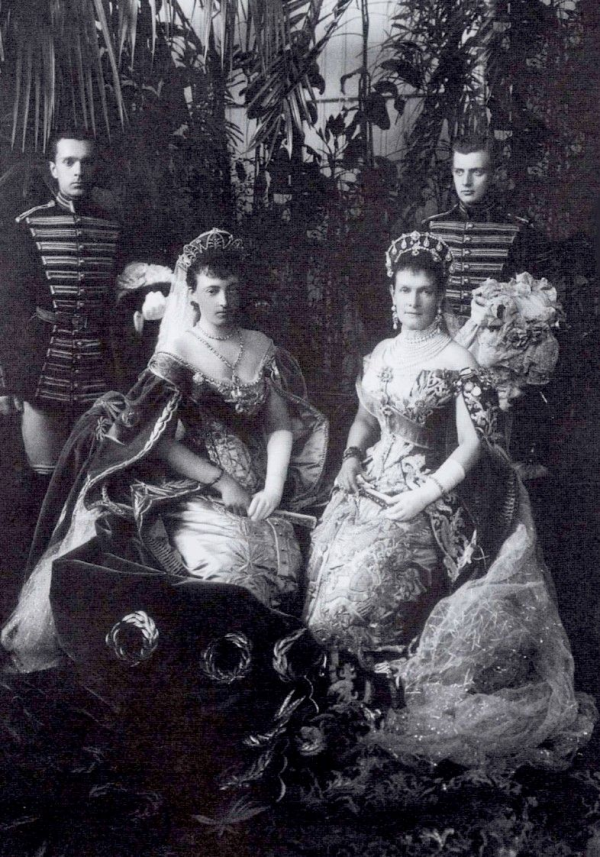

These traditions continued unbroken for a century, culminating with the coronation of the last Russian tsar, Emperor Nicholas II, in 1896. For this coronation, a third imperial crown was made. The consort’s crown, usually placed atop the head of the emperor’s wife during the coronation ceremony, was worn instead by Nicholas II’s mother, Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna. Nicholas’s wife, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, wore a newly-constructed version of the consort’s crown, made for her by court jeweler Karl Hahn and set with diamonds mined in South Africa.

|

| Illustration of “The Russian Crown” on the cover of Puck, 27 December 1905 (Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons) |

Crowns are always a symbol of power. Prince Michael of Greece, an author who has written extensively on crown jewels, has noted that the Russian Imperial Crown is “a symbol, and it’s a way to show your power, your strength, your prestige.” Accordingly, artistic renditions of the crown often exaggerate its qualities for effect, either emphasizing its importance and majesty or using its design as a reflection of the contemporary political environment. During the reign of Nicholas II, the latter was often the case. For example, the illustration above appeared on the cover of Puck, an American magazine that was filled with political satire. Drawn by Carl Hassmann, the imperial crown becomes a twisted, grotesque human skull in this rendering, and the background literally drips with blood. The cover, published in December 1905, was a reaction to increased violence and political instability in Russia, including a failed revolution.

|

| Nicholas II addressing the State Duma, April 1906 (Wikimedia Commons) |

In 1906, the crown appeared in public in an imperial context for the final time. Under pressure after the attempted 1905 revolution, Nicholas made some gestures toward governmental change, including convening a State Duma, a legislative body that was essentially a lower house of parliament. At the opening of the Duma, held in the Kremlin in May 1906, the imperial crown sat to the right of the emperor as he made his opening speech.

Just before the outbreak of World War I, the crown and the rest of the imperial regalia were due for some needed upkeep. Agathon Fabergé, son of Peter Carl Fabergé, took charge of the restoration project, which was undertaken in St. Petersburg. Work was completed on the orb and scepter, but when war was declared in the summer of 1914, the rest of the project stalled. The regalia was returned to the Kremlin Armory.

|

| Detail, display of the Romanov jewels made by the Soviets, ca. 1922 (Wikimedia Commons) |

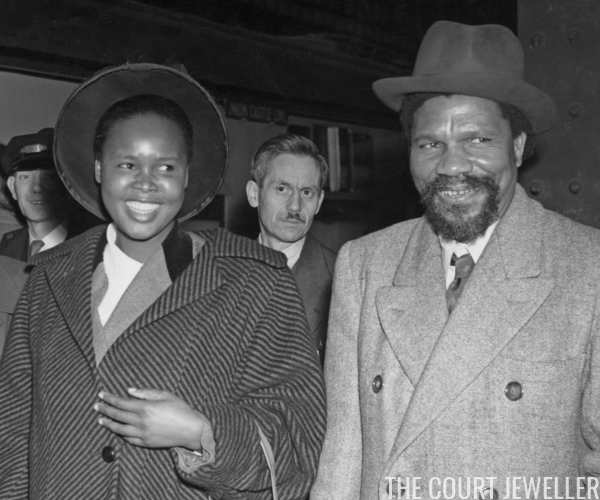

In 1917, the Bolsheviks succeeded in mounting a revolution, overthrowing the monarchy and compelling Nicholas II to abdicate. The emperor and his immediate family were murdered the following year, and the vast riches of the Romanovs were confiscated by the new government. That incredible jewelry haul included the coronation regalia, which was taken out of its home in the Kremlin Armory and displayed with the rest of the confiscated jewels for a famous set of photographs in 1922. The jewels were even shown to members of the foreign press. When Walter Duranty of the New York Times traveled to Moscow in the summer of 1922 to view the arrayed jewels, he was urged to try on the crown himself. He reported that it “wasn’t heavy, but for the moment it felt as if the head were in a balloon into which gas was being pumped under pressure.” (Read more of his article over here!)

|

| The Russian imperial crown, filmed by British Pathé ca. 1922 |

By 1926, the Soviet government was serious about divesting the accumulated riches of the Romanovs. The jewels were filmed and catalogued, and several pieces of state jewelry were sold to a syndicate in England (and then subsequently auctioned at Christie’s in London). The crown itself, however, remained in Russia.

|

| Illustration of the Russian imperial regalia, ca. 1896 (Wikimedia Commons) |

In 1922, the Soviets officially established the Diamond Fund, a collection of precious gems and jewels managed by the Ministry of Finance. The imperial crown is part of this collection, which also includes such priceless gems as the Orloff Diamond and the Shah Diamond.

|

| The Imperial Crown of Russia on display at the Kremlin |

The Diamond Fund is still housed in the Kremlin Armory today, which means that the crown hasn’t strayed at all from the place where it was once used in the middle of elaborate imperial coronations. Much of the treasure of the Romanovs has been scattered or disappeared completely, so this is a rare example of a piece of Russian imperial jewelry that remains, existing as a reminder of the structures of power that came before.