|

| Queen Sofia’s Tiara (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) |

Dior for Charlene at Twickenham

|

| Charlene and Harry watch rugby at Twickenham (Photo: ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images) |

Princess Charlene of Monaco popped over to England this weekend for Saturday’s rugby union test match between England and South Africa. Charlene, who grew up in South Africa, joined a rather famous England supporter, Prince Harry, at Twickenham.

|

| Photo: ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images |

Charlene’s tailored, menswear-inspired ensemble fitted in seamlessly with the sea of be-suited men around here, but she also added a few feminine touches. A red lip and a pair of trendy Dior Tribales earrings completed the look.

|

| Photo: ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images |

Of course, Charlene’s attendance also gives us the rare chance to chat about Harry on the blog. Love the beard!

Jewels on Film: The Crown (Season 1, Episode 2)

Time for another installment of our jewelry recaps of Netflix’s The Crown, everybody! In the second episode of the series, “Hyde Park Corner,” the production has things to say about jewelry, uniforms, and power. (As always, feel free to discuss this episode below, but avoid spoilers for future episodes!)

Last week, we left off at Sandringham at Christmas; we begin this time at the end of January 1952. Philip and Elizabeth are on a plane, ready to touch down in Nairobi for the first stop on their Commonwealth tour. Interestingly, the production did not choose to show the farewell between the couple and the rest of the royal family (and Churchill!) at the airport — which is an iconic scene. But instead, we start with Princess Elizabeth, who is getting ready to greet the people of Kenya.

This is the first of several scenes in the episode where the Queen’s pearls become a major focus. Her dresser is fastening them about her neck here as she practices her speech. She’s literally putting on the uniform of queenship, because she’s there representing her father, and the pearls (as we all know) are a central part of that uniform. And the real three-stranded pearl necklace that this one represents is even more clearly tied to monarchy: it was a gift from the Queen’s grandfather, King George V, to mark his silver jubilee in 1935.

The dress that Claire Foy wears in this scene is based on the real dress that Elizabeth wore when the royal party arrived in Kenya. The hat and jewels, though, are different — except for the pearls. (Here’s some British Pathe newsreel footage, which shows Elizabeth’s outfit and — importantly for what comes next — the attire of the people welcoming her.)

Elizabeth wears lots of ’50s-era earrings in this episode, including this pair. I think most of these are inspired by the era rather than the Queen’s real jewelry box.

The princess is visible nervous, but she makes it through her speech, and then it’s time to do a traditional military review. The Duke of Edinburgh is in full uniform here, too. And he and Elizabeth are faced with many local people in uniform — although Philip has trouble identifying their garb as being just as official and real as his naval uniform. We get our first big “Philip gaffe” in this episode, when he begins to enumerate the medals worn by a representative of the Kipsigis people, noting that he has them as well — and then joking about whether the man stole one of them.

For a shot that lasts for only a few seconds, the production was careful to make the medals symbolically significant. The man Philip speaks with is dressed in native attire, but his medals show that he has made major sacrifices for the Commonwealth and the Crown. Starting on the right, the man wears the War Medal 1939-1945, which means that the man served full-time in the armed forces for at least a month during World War II. (Philip has that one.) Next, the golden star on the yellow striped ribbon is the Africa Star, which means that he fought in the North African Campaign. (Philip has that one, too.) The other star is the 1939-1945 Star, which also honors his World War II service. (Philip has that one as well.)

But here’s the kicker: the medal that Philip jokingly accuses him of stealing — the one on the left, partially obscured by his shell necklace — is the Victoria Cross. The Ministry of Defence notes that the VC is awarded for “most conspicuous bravery, or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy.” It’s only been awarded 1358 times in British history. Philip most certainly does not have this one, and this man, who proudly wears it as he stands before the representative of the Crown, has clearly done something extraordinary to earn it. The look of disgust when Philip accuses him of stealing it is beyond warranted — because Philip is assuming that a Kenyan citizen of the Commonwealth could only have stolen this precious medal, not earned it. This series is trying to put together a rather nuanced portrayal of Prince Philip, and this very brief scene is startling in light of that.

While Philip has trouble recognizing that the Kenyan people wear uniforms that reflect both their own societies and the Commonwealth, Elizabeth is presented as being more aware. When Philip jokes again about the headdress that this Maasai elder wears, she quickly corrects him: it’s not a “hat,” it’s a crown. She’s been struggling to come to terms with the fact that she will soon take on the full uniform of power, and she knows one when she sees it. (If you’re keeping track, then, this is the second crown we’ve seen featured in the show, after last episode’s paper crown. Pay attention; the Maasai crown shows up again.)

After the arrival ceremony ends, the couple travels to Sagana Lodge, where they’ll be staying during their visit. Elizabeth has changed her dress and hat, but her pearl uniform is still firmly in place as she is welcomed, a bit awkwardly, by a child.

Back in Britain, Princess Margaret is also wearing pearls — but she’s secretly, brazenly canoodling with Peter Townsend, not worrying about monarchy. The royal family has decamped to Sandringham after the king’s doctor has given him the all clear. Bertie says he’s feeling better, and he’s having a whale of a time shooting and entertaining — even though Anthony Eden (played by Jeremy Northam) comes to try to convince the king that he should help convince the aging Churchill to step down. In a foreshadowing of what’s to come, the King informs Eden that although Albert Windsor and Churchill were friends, Albert Windsor “was murdered by his elder brother when he abdicated.” King George VI is the sovereign, and he can’t interfere.

On the evening of February 1, the royal family is hosting a dinner party at Sandringham, and the King and Margaret are entertaining their guests with a song. Their selection: “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” from Pal Joey.

Margaret wears a sparkling necklace and earrings as she plays and sings. The song’s about the way that love can surprise even the most jaded sophisticate — an interesting choice, given Margaret’s secret romance with a married man.

And Margaret is surprised here. As her father weakly sings, a single tear trickles down her cheek. Just as Princess Elizabeth and Queen Mary were struck by the King’s mortality during last week’s song, this scene shows Margaret having a similar emotional reaction. It’s unclear precisely what she feels — fear about her father’s health? relief at his recovery? — but she’s moved to tears.

The King gets an enthusiastic ovation from his guests (and from staff gathered outside). And then he watches newsreel footage of Elizabeth’s arrival in Kenya, and then he goes to bed.

(A description of this real-life evening from the Shawcross biography of the Queen Mum: “They had an enjoyable dinner with Princess Margaret; the King was cheerful and his wife was delighted.” In The Young Elizabeth, Kate Williams quotes Princess Margaret, who says they had “jolly jokes” that night. No specific mention of show tunes, but these three — Bertie, Elizabeth, and Margaret — were party-loving people, after all.)

Back in Kenya, Philip and Elizabeth are having a swell time. They’ve been staying overnight at Treetops, where they have a thrilling and terrifying encounter with an elephant. They’re getting along so well, in fact, that Elizabeth sits down to write to her father to ask if they can go back to Malta when the tour is over. On a jewelry note, we get a clear look at Elizabeth’s engagement ring here — and it’s disappointingly nothing like the real one.

If you’re a student of history, though, you know that Elizabeth’s letter is much too late. While she and Philip were at Treetops, the King unexpectedly died in his sleep. Churchill is notified: it’s “Hyde Park Corner,” the government’s code for the king’s death. For the rest of the episode, Churchill struggles with grief — and then triumphs in a remarkable radio address, putting Eden’s plans on the backburner.

We see immediate reactions from three royal women. The Queen Mother is hysterical. Queen Mary is told over her breakfast. It’s so interesting to see these women, who wear such familiar royal uniforms in public, dealing with their grief in their pajamas.

Margaret is paralyzed, listening to the rush through the halls of Sandringham House as the news breaks.

She seeks comfort with Townsend, who promises that he won’t leave her — a tall order, since he was the her father’s equerry. Townsend ends up taking a position with the Queen Mother’s household, over the objections of Tommy Lascelles, a decision that will echo throughout many episodes to come. Lascelles knows what’s up, and even though he basically threatens Townsend, Peter defiantly chooses to remain with the royal family instead of with his own family.

And Princess Elizabeth finally hears the news, too. Philip tells her privately, and then they meet with Martin Charteris to discuss logistics, including her regnal name. Note what’s missing here: Elizabeth is wearing small, era-appropriate earrings, but her pearls are gone. She’s the queen now, but she’s not wearing her uniform yet, because she’s also still just a grieving daughter. She set the pearls aside during her private Treetops holiday, and she has yet to put the uniform back on.

But that’s all about to change. As the car drives Philip and Elizabeth away from Sagana Lodge, a group of Maasai people emerge to watch them go. The camera lingers on one in particular: the elder and his elaborate crown. He watches the new queen go, and the look on his face suggests that he understands better than anyone else what she’s going through.

After she boards the plane that will take her back to London, Elizabeth is still wearing just small ’50s-style earrings (little stylized bows this time) but not her pearls.

But someone else is already back in uniform. Queen Mary writes a compassionate but forthright letter to her granddaughter, giving her advice about her new role and her responsibilities. Mary has clearly gone digging in her jewelry box, because she’s wearing the kind of jet jewelry that was popular during the endless, faddish public mourning of the Victorian era. Nobody really wore jet much in public after the Victoria’s reign ended, but Mary never was a woman to carelessly discard a piece of jewelry.

Her earrings, though, are also set with tiny seed pearls. Pearls are appropriate in numerous situations: with daytime attire, for mourning, and for the regal dress required of a queen.

Elizabeth and Philip’s plane lands, but because her dresser did not pack a black dress, they have to wait for appropriate clothing — the appropriate uniform — to be brought on board before they can walk down the stairs to greet her people. The episode lingers over the process of Elizabeth’s transformation from princess to queen here, showing her undressing and then putting on her mourning attire with the help of her dresser. Here, the camera focuses on the pearls resting in their jewelry box.

And, in an echo of the first scene of the episode, the dresser places them around Elizabeth’s neck — except this time Elizabeth is the monarch, not his representative. It’s not a costume anymore. “The Crown must win,” Queen Mary declares in a voiceover as the pearls are fastened.

For us, of course, it is a costume. The design team has replicated one of the Queen’s most famous outfits here, down to the jewelry. They’ve replicated the shape of the Flame Lily Brooch rather well, but unfortunately, they’ve made it much too big. Here’s a look at the Queen’s real-life ensemble.

Just before Elizabeth deplanes, she’s startled when Tommy Lascelles asks Philip to wait so that “the Crown” can go first. Here, we get our third “crown” of the series: the paper crown, the Maasai headdress, and now Elizabeth herself. She isn’t a just a person anymore; she is the human embodiment of all of the symbols of monarchy now. Albert Windsor was murdered by his brother; Elizabeth Mountbatten died when her father did, a fact that Queen Mary reminds her of in her letter.

We get a better look at the replica Flame Lily Brooch as Elizabeth and Philip travel to Sandringham.

And, of course, when they get there, everything is heartbreaking. The king’s body is laid out on his bed (in uniform, of course). Elizabeth is so overcome when she enters the room that she can’t even make herself look for a few moments.

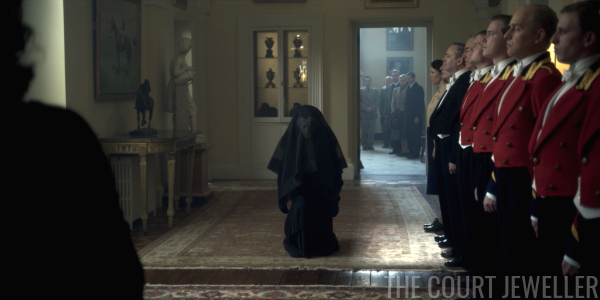

When she emerges, the other Windsor women have their royal jewelry uniform firmly in place, and they begin to observe the traditional rules and regulations of monarchy. The Queen Mother curtseys first…

…and then Princess Margaret, still struggling with the changes, does too.

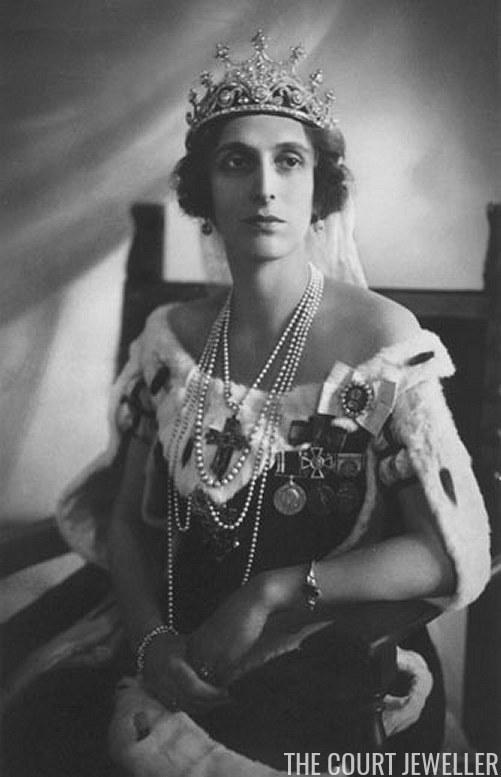

But the most startling curtsey of all comes from Queen Mary, who is an arresting, spectral, Victorian figure in her black gown, jet jewels, and black veil.

Everyone freezes, silently, as the eighty-four-year-old queen sinks slowly in a perfect curtsey.

Elizabeth’s shock and fear is plain on her face.

But Queen Mary just levels her with a serious gaze. These two understand each other, and they know the rules of the game, just as they know what uniforms they must wear to play it. Queen Mary has watched monarchies fall and family members die; she knows strength when she sees it. It should come as no surprise that, in a year’s time, Mary will bequeath an enormous cache of jewelry to her granddaughter. They both know that perception is everything.