|

| Christie’s |

I’ve had so much fun with this virtual tour of royal tiaras in museums, I thought I’d give us one more bonus stop! Today, we’re circling back to Houston, where we find another royal tiara made by Fabergé. This time, the tiara’s owner was a German-British princess who married a Romanov descendant.

|

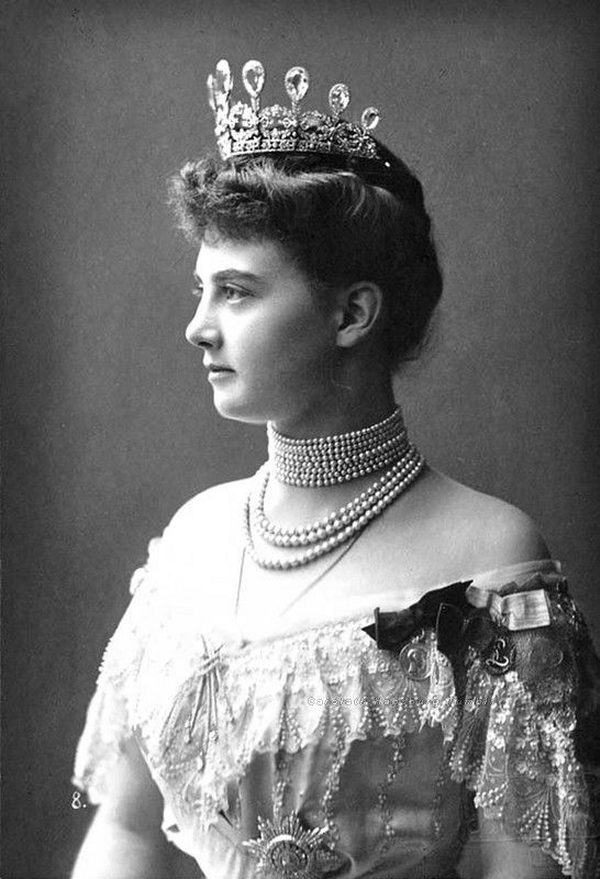

| Grand Duchess Alexandra of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (Christie’s) |

The stunning diamond and aquamarine tiara, made by Fabergé in 1904, belonged to Grand Duchess Alexandra of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. But to fully understand the story of this particular sparkler, we need to travel back a generation, to learn about the woman who engineered its acquisition: Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna of Russia.

|

| Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna, ca. 1878 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna, born in 1860, was easily one of the most fascinating royal women of her generation. The only daughter of Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich and his German-born wife, Duchess Cecilie of Baden, Anastasia was a granddaughter of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. (One of her aunts was a woman we talked about earlier this week: Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, who married the 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg.) Anastasia inherited her mother’s looks as well as her intelligence and her strong, outspoken personality—a trait which often made both women unpopular figures in the royal world of the nineteenth century. She was educated in her mother’s native Germany.

In 1878, the press reported that 18-year-old Grand Duchess Anastasia had been betrothed to Friedrich Franz, the 27-year-old Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. The Mecklenburg-Schwerin family was a familiar one at the Russian imperial court. Four years earlier, Friedrich Franz’s younger sister, Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, had married Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia, Anastasia’s first cousin. The couple’s family connections also stretched back to previous generations. Grand Duchess Anastasia’s grandfather, Tsar Nicholas I, was the brother of Hereditary Grand Duke Friedrich Franz’s great-grandmother, Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna. Both bride and groom were also descendants of King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia: Friedrich Franz was the grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm’s third daughter, Alexandrine, while Anastasia was the granddaughter of his eldest daughter, Charlotte. Newspapers at the time reported that the couple’s mutual cousin, Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany, helped engineer the match.

|

| Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna and Grand Duke Friedrich Franz III of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, ca. 1880 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The marriage took place in chilly St. Petersburg in January 1879. The groom’s family, led by his father, Grand Duke Friedrich Franz II of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, arrived in Russia for the ceremony with a retinue of more than seventy people, including numerous courtiers, his personal physician, and his court chaplain, who would perform the couple’s Lutheran marriage ceremony. Emperor Alexander II led the imperial delegation that met the family at the railway station in St. Petersburg. The imperial wedding festivities were appropriately grand. One contemporary paper reported that the wedding took place at the Winter Palace “according to the Orthodox and Lutheran rites” before all the “dignitaries of the State.” Afterward, “A banquet in honour of the event was given, and on each toast being proposed there was a salvo of artillery—altogether 206 guns being fired.” The festivities also included special Te Deum services, a ball at St. George’s Hall, and illuminations.

|

| Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, ca. 1889 (Wikimedia Commons) |

The marriage produced three children: Alexandrine, Friedrich Franz, and Cecilie. But it wasn’t a particularly happy union. Friedrich Franz, who succeeded to the throne as Grand Duke Friedrich Franz III in 1883, preferred the company of men. He also suffered from lingering health problems, including serious asthma and conditions of the skin and the heart. His medical issues, combined with Anastasia’s dislike of Schwerin, led them to travel often to warmer climates. They were in Palermo when Anastasia gave birth to the next Mecklenburg-Schwerin grand duke, the future Friedrich Franz IV, in 1882. After Friedrich Franz III’s accession, the family divided their time between Schwerin, where they lived during the summer months, and Cannes, where they purchased a home, Villa Wenden, on the Mediterranean.

Anastasia also remained a vital member of the Russian imperial family. At the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra in 1896, she dressed a splendid imperial court gown and jewels, riding in a golden state coach with the Queen of the Hellenes (Grand Duchess Olga Constantinovna), the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna), and Grand Duchess Vladimir (her sister-in-law, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna).

|

| Grand Duchess Anastasia with her three eldest children, Duchess Cecilie, Duchess Alexandrine, and Grand Duke Friedrich Franz, ca. 1890s (Wikimedia Commons) |

In 1897, however, the family faced tragedy. After years of medical problems, Grand Duke Friedrich Franz III’s health took a turn for the worse at Villa Wenden. He died there in April 1897, but the exact circumstances of his death are shrouded in mystery. Shortly after his death, papers published contradictory accounts of the grand duke’s final moments. All agreed that he died after suffering a fall somewhere on the grounds of the villa or nearby. Some wrote that the fall was a deliberate act, an attempt to end the immense physical suffering he was enduring. Others declared that the fall was accidental.

The late grand duke was succeeded by his 15-year-old son, Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV. Because he was still a minor, his uncle, Duke Johann Albrecht, served as regent until his eighteenth birthday. While the young Friedrich Franz was busy with his studies, first in Dresden and then in Bonn, his mother and sisters largely stayed in Cannes. There, in 1898, his sister Alexandrine married Prince Christian of Denmark, who would eventually reign as King Christian X. Four years later, his mother caused a major scandal. In her widowhood, she had begun an affair with her secretary, Vladimir Alexandrovitch Paltov. In December 1902, she gave birth to his son at the villa in Cannes. She named the baby Alexis Louis de Wenden, with a surname inspired by her home.

Contemporary newspapers got wind of the fact that something strange was going on with the widowed grand duchess, but for a time they couldn’t quite pin down the correct reason for the scandal. One reported that she had been banished from court in Mecklenburg because she’d carried on an affair with “a young hairdresser.” Another reported that she had gone into retirement because of an attack of the measles, though “the gossips on the Riviera look wise and are hinting about the blood of Catherine of Russia running in her veins.” Eventually, by February 1903, as Grand Duke Friedrich Franz and his Russian imperial uncles headed to Cannes, papers in America were becoming more forthright about the rumors: “Within the last few days a famous Berlin gynecologist was in attendance on the Grand Duchess. The only possible inference is that she has given birth to a child, and the Grand Dukes are assembling to hold a family council to decide on the future of the child.” Ultimately, Anastasia was allowed to raise her son herself.

|

| Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (Wikimedia Commons) |

The shocking birth of the half-brother of Anastasia’s Mecklenburg-Schwerin children didn’t have much of an affect on their own status within the world of Europe’s royals. By December 1903, Friedrich Franz had good news of his own to share. He was engaged to be married to an eligible German princess: Princess Alexandra of Hanover, the daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland. The union would not only create ties between Mecklenburg-Schwerin and another German royal family; it would also bring the family closer to the British royals.

|

| The Duke and Duchess of Cumberland ca. 1888 with their children: (L-R) Prince George William, Princess Marie Louise, Prince Christian, Prince Ernst August, Princess Alexandra, and Princess Olga (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Duke and Duchess of Cumberland were part of the exiled former royal family of Hanover, who lost their throne in 1866 when Prussia annexed the kingdom. Crown Prince Ernst August, Duke of Cumberland was the only son of the last Hanoverian king, George V. He was also a British prince, thanks to his grandfather, King George III’s fifth son, Prince Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. Ernest Augustus had become King of Hanover in 1837, thanks to Salic laws of succession that wouldn’t permit a woman (in this case his niece, Queen Victoria) to ascend to the Hanoverian throne.

In 1875, while visiting the Prince and Princess of Wales at Sandringham, Ernst August met Princess Thyra of Denmark, sister of the Princess of Wales. They married three years later, settling in Austria, where their six children were born. Coincidentally, Princess Thyra, like Grand Duchess Anastasia, had also given birth to a secret child. As a teenager, she had fallen in love with a handsome cavalry officer, and had secretly given birth to a daughter. The child was adopted by a Danish family.

|

| Princess Alexandra of Hanover, ca. 1900 (Wikimedia Commons) |

Though Princess Alexandra’s family home was Schloss Cumberland in Gmunden, Austria, she spent quite a lot of time with her Danish royal relatives—including Friedrich Franz’s sister, Princess Alexandrine, who was married to Alexandra’s cousin, Prince Christian. Friedrich Franz and his sister Cecilie also began spending a great deal of time at the Danish court. The press soon figured out that he was likely to marry one of the young women in the Danish royal circle. At first, they speculated that Princess Thyra of Denmark, Prince Christian’s sister, was the object of his affections.

By the beginning of December 1903, though, the press had figured out the identity of Friedrich Franz’s real future bride. The British magazine Truth wrote: “It is understood that a marriage is likely to take place between the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and the Princess Alexandra of Hanover, second daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland, and their betrothal, which was privately arranged in October at Fredensborg Castle, will soon be officially announced.”

A few weeks later, papers were full of the news of the engagement, which was announced from Alexandra’s parents’ home in Gmunden. The announcement, one paper wrote, “has caused hearty rejoicing at the Villa Wenden,” and “no less rejoicing” at the home of Friedrich Franz’s Russian grandfather, Grand Duke Mikhail, “who is overjoyed at the happy event.” The New York Times reported that the union had “the advantage of mutual inclination on the part of the bride and the bridegroom.” (No such feelings of affection existed between Princess Alexandra and one suitor she was pressured to accept—the Crown Prince of Germany, who would go on to marry Friedrich Franz’s sister, Duchess Cecilie.) Because Alexandra was a British princess, permission also had to be granted by King Edward VII, who gave his assent to the marriage.

|

| Wedding portrait of Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Princess Alexandra of Hanover, June 1904 |

The royal wedding took place on June 7, 1904, in Gmunden. The 22-year-old groom wore military dress; the 21-year-old bride topped off her bridal ensemble with the petite diamond nuptial crown that had belonged to Queen Charlotte of the United Kingdom. A civil ceremony was held first at Schloss Cumberland, with the Duke of Cumberland and Duke Johann Albrecht of Mecklenburg-Schwerin serving as witnesses. Later in the day, a religious wedding took place at Gmunden’s Protestant church. The celebrations were attended by numerous royal guests, including Grand Duchess Anastasia, Prince Christian and Princess Alexandrine of Denmark, Duchess Cecilie, as well as the bride’s grandfather, King Christian IX of Denmark, her parents and siblings, and her brother-in-law, Prince Max of Baden.

The ceremony had nearly been postponed when Alexandra’s aunt, Princess Marie of Hanover, suddenly died three days before the wedding; however, the family decided to move the late princess’s remains to another nearby villa, have the wedding, and then inter the body afterward. The late princess had specifically requested before her death that the wedding not be delayed as a result of her passing.

|

| Christie’s |

As a wedding gift, Friedrich Franz offered his wife a remarkable piece of jewelry sourced from his mother’s native Russia. Indeed, Grand Duchess Anastasia seems to have taken the lead in procuring a tiara for her new daughter-in-law from Fabergé. Correspondence between the government of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and the jewelry firm reveals that several designs were proposed, and that a diamond and aquamarine tiara was delivered for the princess shortly after their royal wedding in June 1904.

The tiara’s elaborate diamond base features numerous elements typical of belle époque style, including forget-me-knots and ribbons. You’ll also note that the large, pear-shaped aquamarines are set atop cupid’s arrows — a touching design element for a tiara given as a wedding present.

|

| Grand Duke Friedrich Franz and Grand Duchess Alexandra (Christie’s) |

After their wedding, the Grand Duke and Grand Duchess embarked on a honeymoon, part of which was spent attending the Gordon Bennett Cup, a motor race held in Germany. (Friedrich Franz was an automobile enthusiast.) Shortly after she received the tiara, Alexandra wore the diadem for a grand court ball in Schwerin, held in July 1904. The Christie’s catalogue notes that “Princess Alexandra was recorded wearing a pink silk dress with pearl necklaces and an aquamarine tiara” for the event. Around the same time—perhaps even the same evening—Friedrich Franz and Alexandra sat for a series of photographic portraits, which feature Alexandra wearing her new tiara.

|

| Grand Duchess Alexandra of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, ca. 1904 (Grand Ladies Site) |

Friedrich Franz and Alexandra did apparently have a contented marriage, with five children born between 1910 and 1922. But, of course, their lives were also a time of great change and upheaval for the royals of Europe. In 1917, Alexandra’s British royal status was removed by King George V. The following year, Friedrich Franz was compelled to abdicate at the end of World War I. The family moved to Denmark for a time, but ultimately they were allowed to return to Schwerin and even recovered some of the property that had been stripped from them. The family was divided politically and geographically during World War II. Friedrich Franz IV died in November 1945, only a few months after the war’s end, while Alexandra lived until 1963. After her death, her descendants inherited her diamond and aquamarine tiara.

|

| Christie’s |

In May 2019, Grand Duchess Alexandra’s sparkling Fabergé tiara was offered for sale at Christie’s in Geneva. The auction house anticipated that the tiara would sell for between $200,000-300,000. When the hammer fell, though, the piece had far exceeded that estimate, selling for just over $1,020,000.

|

| Faberge tiaras on display in Houston (Photo generously shared with us by Jeanne; do not reproduce) |

Royal jewel lovers breathed a sigh of relief when they learned the identity of the tiara’s new owners: Dorothy and Artie McFerrin, who own one of the largest private collections of Fabergé in North America. They generously share their bejeweled bounty with the public through a collaboration with the Houston Museum of Natural Science, which features a permanent gallery of pieces from the McFerrin collection. The tiara joins two other spectacular Fabergé diadems in the display: the Leuchtenberg Fabergé Tiara, once owned by Queen Marie-Jose of Italy, and the Westminster Blue Enamel Kokoshnik. One of our lovely readers made a pre-pandemic visit to the museum, and kindly shared the photo of the three tiaras with us. How wonderful to have such sparkling royal history available to visit here in America!

Have you had the chance to see Grand Duchess Alexandra’s tiara in Houston?

Leave a Reply